Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly

Formerly "Picture of the Month"

May-June 2007

The Greening of Pragmatism (II)

(Reflections on Critical Pragmatism, Part 5)

The greening of pragmatism (ii): current issues in developing critical pragmatism a methodological trilemma In the previous discussion, we explored the emergence of different notions of "critical pragmatism" in the literature of various fields. It is time now to turn our attention from history to the present. Given the findings of our historical review, what critical thoughts offer themselves and what are the challenges ahead?

|

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

Where do we stand in developing critical pragmatism? Some critical comments Our review in the last Bimonthly (Ulrich, 2007b) found that the term "critical pragmatism" is emerging from two different but mutually influential strands of thought. On the one hand it has been used in the fields of cultural and educational theory as well as planning theory, on the other hand in social theory and philosophy. In the fields of cultural, educational, and planning theory, critical pragmatism often stands for a reformist commitment to an open, pluralist society in which all people can participate equally and meaningfully; it is essentially a project of social change. In the fields of social theory and philosophy, by contrast, critical pragmatism basically stands for a methodological interest in bringing together the traditions of pragmatist and critical thinking; it is mainly a philosophical project.

To be sure, the two strands of thought cannot be neatly separated; societal visions and philosophical efforts may (and usually do) motivate and support one another. That does not imply, however, that critical pragmatism as a philosophical project is necessarily to be associated with any particular ideological perspective. I suggest we should be careful about doing so. Whilst a philosophical effort is always well advised to reflect on the ideological implications it may have that is, to subject its findings and conclusions to ideology-critique it should hardly begin by defining its ends and scope of inquiry in ideological terms. Wearing such ideological blinkers would run counter to the spirit of ideology-critique.

Hence, my bias is in favor of a methodological rather than an ideological understanding of critical pragmatism. Although I sympathize with many of the concerns of the reformist (or social change) strand, my plea is for a philosophical (and social theory) understanding of critical pragmatism. Such an understanding need not prevent us from engaging in projects of educational, cultural, and political reform, but it may better prepare us for them. It has its own dangers though. In particular, we must not allow it to become an end in itself, a mere project of social theory building that would remain remote from all practice. Just as the reformist (or social change) strand of critical pragmatism risks raising practical claims that it cannot justify philosophically, the philosophical (or social theory) strand risks advancing concepts of practical reason that do not lend themselves to practice, as it has happened, for example, with critical theory's concepts of rational "practical discourse" and "discourse ethics."

A few additional comments, directed more specifically at the work of the authors whom we found representative of the two strands of critical pragmatism, may be useful to further clarify the ways in which my proposed notion of critical pragmatism tries to avoid these two traps.

On the reformist (or social change) strand of critical pragmatism If (as I have just argued) we mean by critical pragmatism primarily a philosophical project, although not as an end in itself, the term itself suggests a basic definition:

Critical pragmatism is the endeavor to promote a critical understanding and practice of pragmatism. (My proposed basic definition)

If however we mean by critical pragmatism primarily a program of reformist social action, we have no choice but to define it in the terms of the specific ideology and/or practical commitments that guide some particular author(s) or social activist(s), for instance along the lines of Mary Jo Deegan's (1988, p. 26) definition of Jane Addams' (1902, 1910) critical pragmatism:

Critical pragmatism [as implicit in the writings of Jane Addams] is a theory of science that emphasizes the need to apply knowledge to everyday problems based on radical interpretations of liberal and progressive values. Deegan (1988, p. 26)

This definition may accurately capture the spirit of the writings of Jane Addams and (to a lesser degree) those of other authors whom we associated with critical pragmatism, such as John Dewey (e.g., 1909, 1916, 1925, 1937) and Alain Locke (1925, 1933, 1936, cf. Harris 1999), although neither of them (as far as I am aware) has used the term. The term is aptly chosen in that pragmatist thinking is clearly present in their works and goes hand in hand with a critical social engagement. This is particularly true with regard to Jane Addams and John Dewey's cooperation on social and pedagogical projects, so that it is surely not inadequate to characterize their critical social engagement as an attempt to live pragmatist philosophy as a critical (in the sense of social-reformist) practice of pragmatism.

Nevertheless, this biographic employment of the term should not have us misunderstand the "critical" intent of critical pragmatism primarily in such political terms, as if it depended on a particular program of political and social action. That would render critical pragmatism unattractive to all those who may not share that particular program of action. It would from the outset compromise its chances to promote reflective research practices in the social sciences and the applied disciplines. It would also run counter to the epistemological and methodological intent of critique as a philosophical concept, the point of which is ideology-critique and quite generally a self-reflecting and transparent way of handling the normative underpinnings and implications of our claims.

It is of course true that we can never quite free ourselves of all ideological assumptions, nor do I mean to suggest we should. This holds true for a "critical" stance as much as to any other. So long as we lay our normative position open and reflect on the way it conditions our claims, there is no reason why a personal ideological commitment should be incompatible with pragmatist thinking. This also applies to John Forester's (1993, 1998, 1999) use of the label "critical pragmatism" for his work on planning theory and practice. The point of my reservation is not that I do not sympathize with his participatory and emancipatory, at times radical-reformist view of planning; I do. The point is only that a "critical" social and political engagement furnishes no adequate definition characteristic of critical pragmatism, no more than any other ideological stance, for it is methodologically arbitrary. Adopting a normative position as such constitutes no methodological achievement and defines no methodological project. It tells us little about the philosophical issue that motivates this series of reflections, of how we can methodologically recover and develop pragmatist philosophy as a tool of critical inquiry and practice (compare Ulrich, 2006a-c).

In conclusion, this first strand of critical pragmatism is of limited interest for the philosophical project that I associate with critical pragmatism; for this project is "critical" in a philosophical and methodological sense rather than in the sense of a predefined political and ideological stance. Only thus can it help us revive pragmatist philosophy as a framework for reflective research.

On the philosophical (or social theory) strand of critical pragmatism Turning now to the second strand, its central idea of building a bridge between critical social theory and pragmatism is obviously much closer to my own understanding of critical pragmatism. This same idea has for some 30 years been among the motives for my work on critical systems heuristics and boundary critique, although in a way that is somewhat different from my present interest in critical pragmatism. My original interest was mainly in "pragmatizing" critical theory (especially its discursive concept of practical rationality), whereas my present interest drawing on my earlier work is mainly in promoting a critical turn of pragmatism.

It appears that the perspective that currently prevails in this emerging second strand of critical pragmatism focuses on the idea of a pragmatist revision of critical theory (see, e.g., Dryzek, 1995, and White, 2004). Nonetheless, I do not think we would be well advised to equate critical pragmatism with an attempt to revise critical social theory. I am concerned not only because revising critical theory is a rather bold venture, one that may not produce a satisfactory result very soon and to which in any case I would not want to lay claim; I am also concerned because due to its theoretical nature, such a meta-critique of critical theory risks once again sacrificing the quest for critical practice the pressing task of providing methodological support to reflective practitioners to academic theorizing about practice. As much as it is philosophically relevant to explain whether and how a critical theory of society is possible and can provide systematic orientation to the practice of research (especially in the social sciences and applied disciplines), this is not the kind of "pragmatic" support that practicing researchers and professionals, managers, politicians, and concerned citizens usually tell us they need in the first place. More urgent to them are down-to-earth tools that not only philosophers and social theorists understand but which a majority of people can use as guides to reflective practice.

Of course the assumption that has always been driving the development of critical social theory is that sound theory eventually translates into sound practice. That may be true, at least in the negative sense that poor theory is rarely conducive to good practice. But as we have seen in an earlier reflection (Ulrich, 2006d), the reverse assumption is not automatically true: sound theory does not ensure sound practice. Not even the best theory can ultimately make sure that people find peaceful and fair ways of handling their differences. Critical theory may support but cannot supersede efforts to develop practical conceptual tools and, with their help, to foster the reflective and argumentative skills of ordinary people.

However, I certainly agree with the conclusion that John Dryzek (1995) has drawn from a review of critical theory's achievements as a research program:

Clearly, there can be more to critical theory than the aridity and abstraction with which empirically oriented social scientists often dismiss it. Indeed, critical theory points to a rich and important conjunction of social theory and empirical research. Yet there remains a shortfall between the programmatic statements of Habermas and other critical theorists on the one hand, and what has actually been accomplished in terms of putting critical theory into social science practice on the other. The situation can be corrected to the extent critical theorists come down from the metatheoretical heights to actually practice the critique they preach. There is no shortage of work for those interested in critical theory as a research program. (Dryzek, 1995, p. 115f)

Challenges ahead: a methodological trilemma There is no shortage of work to be done indeed. Let us then turn to the methodological challenges ahead. It seems to me Dryzek's conclusion raises two basic issues. The one concerns the gap between the theory and the practice of research, the other (within the realm of theory) the gap between the critical and the pragmatic traditions of thought on the nature of research. I'll begin with the second gap, as overcoming it may be our best current chance for overcoming the first gap.

Bridging the gap between critique and pragmatism Dryzek's (1995) call for a more strongly "applied" orientation of critical theorists has recently been taken up by White (2004; compare the previous Bimonthly for a short account). Although these two authors argue mainly within the context of American political science and moreover do not use the term "critical pragmatism," I find their conjectures about a pragmatist revision of critical theory relevant to our present discussion. While our discussion thus far emphasizes the need and potential for accomplishing a critical turn of pragmatism (the "greening" of pragmatism, Ulrich 2007b), theirs emphasizes the need and potential for accomplishing a pragmatist turn of critical social theory.1) It seems to me these two projects are complementary in that they both depend on the same basic assumption, namely, that there are sufficient methodological affinities between the two traditions of critical and pragmatist thought to warrant a marriage. This makes it meaningful for the two projects to learn from one another.

I will discuss some of the affinities in question in the next contribution to this series; at this point it may suffice to say that I believe there are indeed sufficient affinities between critical theory and pragmatism, provided we recognize the need not only for a pragmatist turn of critical theory (as suggested by Dryzeck and White) but also, at the same time, for a critical turn of pragmatist philosophy. Only thus can we expect the marriage to be successful. If it were otherwise, it would be difficult to explain why thus far, nobody has come up with the kind of pragmatist critical theory that Dryzek and White are calling for.

In addition, it is conspicuous that both critical theory and pragmatist philosophy suffer from considerable deficits of application. The application deficits of critical social theory, both as a model of critical social science and as a model of discursive ethics, are as obvious as is the failure of contemporary pragmatist philosophy to develop a methodologically strong tradition of critical practice. I suspect this shared deficit is not entirely accidental but is rooted in common methodological difficulties a negative methodological affinity, as it were. I am thinking, for example, of their shared dependence on ideal conceptions of rationality, in the form of completely rational discourse (in the case of critical theory) and of comprehensively explored consequences (in the case of pragmatism). This leads us back to the first gap mentioned above, that between theory and practice.

Bridging the gap between theory and practice Whether we prioritize a pragmatist turn of critical theory or a critical turn of pragmatist thought or see the two projects as inseparable, any of these philosophical projects must at some point translate into practice. A well-understood critical pragmatism will not sacrifice the task of supporting reflective practice to some mainly theoretical ambitions;2) its focus will be neither exclusively theoretical nor exclusively practical. I would suggest such a two-dimensional perspective is best ensured if we understand the idea and tradition of reflective practice as a third basic resource of critical pragmatism, one that raises its own specific issues and for this reason cannot be reduced to either critical theory or pragmatist thought or both.

This third relevant tradition is often associated with Donald Schφn's (1983, 1987) influential work on the reflective practitioner; but unfortunately, it has taken a largely subjectivist or psychological turn and thereby tends to avoid the crucial methodological question of how reflective practice can ensure a critical handling of practical rationality claims as they inevitably arise in practice for instance, claims to accurate and relevant knowledge, to adequate assessment of situations, to effective and efficient action, and to ethically defendable consequences. This is important because reflective practice implies such claims no less than any other practice. To a large extent, the stuff of reflective practice is the handling of uncertainties and conflicts about such claims. We need not enter into a discussion of this essential shortcoming of the prevailing concept of reflective practice (I have offered such discussion elsewhere, see, e.g., Ulrich, 2000 and 2001) to understand that an adequate concept of reflective practice raises "applied" philosophical issues that cannot be reduced to self-reflection in the prevalent psychological sense of mainstream thought on reflective practice (see, e.g., the specialized journal Reflective Practice), as little as to the theoretical conceptions of comprehensively rational practice in critical theory and pragmatist philosophy.

For instance, while critical theory cannot hope to explain rational practice without assuming conditions of complete rationality, that is, conditions that in principle (although they rarely if ever obtain) would allow us to justify all the claims involved, reflective practice must try to promote better practice by helping people to handle the less-than-ideal conditions of rationality here and now, in concrete contexts of (imperfectly rational) action. Likewise, critical theory cannot hope to elucidate the meaning of moral action without explaining the principles that (ideally) would allow us to claim moral perfection, whereas reflective practice can at best help people to achieve a reasoned state of moral imperfection (Ulrich, 2006a, p. 55). Similarly, while pragmatist philosophy cannot explain a proposition's pragmatic meaning and merit without assuming a comprehensive effort of clarifying that proposition's conceivable consequences, reflective practice must try to support people in dealing with the fact that a comprehensive consideration of all conceivable consequences is usually beyond our possibilities.

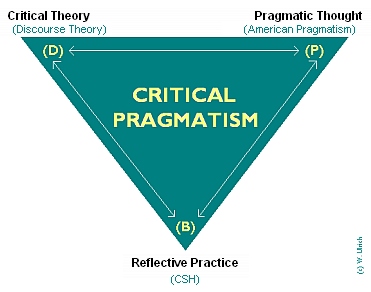

A methodological trilemma of critical pragmatism My conclusion from these considerations is that we can usefully situate critical pragmatism in the center of three research traditions: critical theory, pragmatic thought, and reflective practice. They constitute the inseparable trio of critical pragmatism, as it were. Each of them furnishes an indispensable source of reflection on some essential methodological difficulties of critical pragmatism and also contributes some valuable ideas to their solution. Each also brings to the party its own specific difficulties that is has been unable to overcome on its own and which thus call for a revision of its methodological assumptions. We have, then, three essential cornerstones of critical pragmatism as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Three methodological cornerstones of critical pragmatism

(D) Discursive principle; (P)

Pragmatic maxim; (B) Principle of boundary critique

The three cornerstones are so closely interdependent that it would make little sense to conceive of "critical pragmatism" in terms of any one or two of the three cornerstones only. The methodological considerations and principles they offer are not only equally essential for developing critical pragmatism, they also can mutually support one another. For example, critical theory elucidates the importance of the discursive principle; pragmatist thought sheds light on the importance of the (often neglected) pragmatic maxim; and reflective practice as conceived in critical heuristics makes us understand the importance of the principle of boundary critique. All three principles are fundamental to my notion of critical pragmatism; yet it seems to me none can be fully redeemed without the help of the others.

This is so because each the three cornerstones raises methodological difficulties that cannot be met without assuming some solutions to the other two; in so far, the triangle represents a methodological trilemma. In my work on critical heuristics, I have found the following methodological core issues to be fundamental, and fundamentally interdependent, for dealing with the three corners of the triangle: the problem of practical reason for pragmatizing critical theory; the dilemma of holism for operationalizing pragmatist thought; and the need for a critical turn of our concepts of rationality, truth, and ethics as a basis for developing some critical heuristics of reflective practice. Again, this is not the place to discuss these issues in any detail; I merely want to point out that since the three issues are interdependent, chances are we will resolve them together or not at all. That is what I mean with the "methodological trilemma" of critical pragmatism as suggested in Figure 1.

As a last note, Figure 1 also makes it obvious that not all researchers interested in developing critical pragmatism need to have the same priorities and to speak of exactly the same methodological challenges all the time. Each of the figure's three corners may serve as a starting point, so long as we do not lose sight of their close interdependence. So long as researchers keep this methodological trilemma in mind, they will help the cause of advancing critical pragmatism by approaching it from any of the three research traditions, as well as by relating it to other philosophical traditions.3)

Conclusion The proposed notion of critical pragmatism differs from some of the previous notions that I have found in the literature in three basic ways:

- It understands "critique" in a methodological rather than an ideological sense.4)

- It attributes equal weight to the two complementary perspectives of giving philosophical pragmatism a more critical face (i.e., pursuing a critical turn of pragmatism) and of giving critical theory a more pragmatic face (i.e., pursuing a pragmatist turn of the tradition of "critique").

- It focuses as much on the practical requirements of reflective practice as on the theoretical requirements of critical theory and pragmatist philosophy, whereby "practice" refers both to "applied science and expertise" and to "practical reason" in a Kantian, ethical, sense.5)

Integrating the application of theoretically based science and expertise with practical reason recovering the Kantian conception of the inextricable two-dimensionality of reason may well be the core challenge that critical pragmatism is all about. As Jurgen Habermas reminded us long ago:

The capacity for control made possible by the empirical sciences is not to be confused with the capacity for enlightened action. The scientific control of natural and social processes in a word, technology does not release men from action. Just as before, conflicts must be decided, interests realized, interpretations found through both action and transaction structured by ordinary language. Habermas (1971, p. 56)

Notes

1) I find Dryzek (1995) and White's (2004) concern very much parallel to that of my earlier work on critical systems heuristics (CSH). They aim at an opening of contemporary American political science to critical theory and to this end find it necessary to look for some pragmatization of critical theory; similarly, my work on CSH aimed at an opening of systems thinking, and of the professional practice informed by it, to critical theory, with a consequent focus on pragmatizing critical theory in the form of "critical systems heuristics." [BACK]

2) On my related reservations against relying on critical theory alone, see Ulrich, 1983 (Ch. 2, esp. the final section titled "Conclusions: Critical Theory or Critical Heuristics?") and 2006. [BACK]

3) With hindsight, much of my work on critical systems heuristics and boundary critique has consisted not only in exploring methodological affinities among the three cornerstones but also in trying to understand them in the light of what other traditions have to say, notably Kant's (1781, 1785, 1788) critical philosophy (especially his practical philosophy), Popper's (1959, 1963, 1972) critical rationalism (especially his model of critically-rational discussion), and the tradition of systems thinking (especially Churchman's [1971, 1979] philosophy of social systems design). [BACK]

4) On the importance of a methodological rather than ideological understanding of "critique," compare my analysis of the role of the "emancipatory interest" in critical theory and critical heuristics in Ulrich (2003, pp. 332-339). [BACK]

5) Compare the practical-philosophical twist that I have given the pragmatic stance in my recent critique of the "primacy of theory" doctrine in mainstream science theory (see Ulrich, 2007a and more fully 2006c): methodologically speaking, a focus on practice also means to recover the Kantian "primacy of practice" (i.e., of practical-normative reason) against the Popperian "primacy of theory" (i.e., of theoretical-instrumental reason). One of the basic aims that I associate with critical pragmatism is indeed to recover for pragmatic thought Kant's lost notion of the two-dimensional character of reason, according to which reason is always theoretical and practical reason at the same time. It is only because this notion has been lost in mainstream science theory and has also remained underdeveloped in American pragmatism, that today we have to rediscover it and have to assure ourselves that "theoretical argumentation is not coextensive with the reach of rational argumentation in general" (Ulrich, 2007a, concluding section). [BACK]

References

Addams, J. (1902). Democracy and Social Ethics. New York: Macmillan.

Addams, J. (1910). Twenty Years at Hull House, with Autobiographical Notes. New York: Macmillan.

Churchman, C.W. (1971). The Design of Inquiring Systems. New York: Basic Books.

Churchman, C.W. (1979). The Systems Approach and Its Enemies. Basic Books: New York.

Deegan, M.J. (1988) Jane Addams and the Men of the Chicago School, 1892-1918. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Dewey, J. (1909). Moral Principles of Education. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan.

Dewey, J. (1925). Experience and Nature. La Salle, IL: Open Court.

Dewey, J. (1937). Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. Wiley: New York.

Dryzek, J.S. (1995). Critical theory as a research program. In S.K. White (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Habermas, Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 97-119.

Forester, J. (ed.) (1993). Critical Theory, Public Policy, and Planning Practice: Toward a Critical Pragmatism. State University of New York Press: Albany, NY.

Forester, J. (1998). Rationality, dialogue, and learning: What community and environment mediators can teach us about the practice of civil society. In M. Douglass M. and J. Friedman (eds), Cities for Citizens: Planning and the Rise of Civil Society in a Global Age, New York: Wiley, pp. 213-226.

Forester, J. (1999). On Not Leaving Your Pain at the Door: Political Deliberation, Critical Pragmatism, and Traumatic Histories. In J. Forester, The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 201-220.

Habermas, J. (1971). Technical progress and the social life-world, in J. Habermas, Toward a Rational Society, Boston, MA: Beacon Press, pp. 50-61.

Harris, L. (ed.) (1999). The Critical Pragmatism of Alain Locke: A Reader on Value Theory, Aesthetics, Community, Culture, Race, and Education. Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD.

Kant, I. (1781). Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Norman Kemp Smith. New York: St. Martin's Press 1965 (orig. New York: Macmillan, 1929).

Kant, I. (1785). Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals. Translated and analyzed by H.J. Paton. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1964.

Kant, I. (1788). Critique of Practical Reason and Other Writings in Moral Philosophy. Translated and edited with an introduction by Lewis White Beck. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1949.

Locke, A.L. (ed.) (1925). The New Negro: an Interpretation. New York: Albert and Charles Boni.

Locke, A.L. (1933). The Negro in America. Chicago: American Library Association.

Locke, A.L. (1936). Negro Art - Past and Present. Washington, D.C.: Associates in Negro Folk Education.

Popper, K.R. (1959). The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchinson: London.

Popper, K.R. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London and New YorK. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Popper, K.R. (1972). Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach. Oxford, UK, and New York: Clarendon / Oxford University Press. Rev. ed. 1979.

Schφn, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

Schφn, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland: Haupt. Reprint ed. Chichester, UK, and New York: Wiley, 1994.

Ulrich, W. (2000). Reflective practice in the civil society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268

Ulrich, W. (2001). The quest for competence in systemic research and practice. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 18, No. 1, pp. 3-28.

Ulrich, W. (2003). Beyond methodology choice: critical systems thinking as critically systemic discourse. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 54, No. 4 (April), pp. 325-342.

Ulrich, W. (2006a). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional and business ethics. In L. Zsolnai (ed.), Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business Ethics, Vol. I. Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, and Bern, Switzerland, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich, W. (2006b). A

plea for critical pragmatism. (Reflections

on critical pragmatism, Part 1). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, September-October 2006.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2006.html

Ulrich,

W. (2006c). Rethinking

critically reflective research practice: beyond Popper's critical

rationalism. Journal of Research

Practice, 2, No. 2 (October), article P1.

[HTML] http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/64/63

Ulrich, W. (2006d). Theory and practice I: beyond theory. (Reflections

on critical pragmatism, Part 2). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, November-December 2006.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2006.html

Ulrich,

W. (2007a). Theory

and practice II: the rise and fall of the "primacy of theory."

(Reflections on critical pragmatism, Part 3). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, January-February 2007.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_january2007.html

Ulrich, W. (2007b). The greening of pragmatism

(i): the emergence of critical pragmatism. (Reflections on critical pragmatism, Part 4). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, March-April 2007.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2007.html

White, S.K. (2004). The very idea of a critical social science: a pragmatist turn. In F. Rush (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 310-335.

|

May 2007 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

June 2007 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Picture data Digital photograph taken on 28 May 2004 at 8 p.m., shutter speed 1/50, aperture f/4.5, ISO 50, focal length 19.25 mm (equivalent to 86.25 mm with a conventional 35 mm camera). Original resolution 2272 x 1704 pixels; current resolution 700 x 496 pixels, compressed to 103 KB.

We can situate critical pragmatism in the center of three research traditions: critical theory, pragmatic thought, and reflective practice. They constitute the inseparable trio of critical pragmatism.

(From this reflection on the nature of critical pragmatism)

Notepad for capturing personal thoughts »

|

Personal notes:

Write

down your thoughts before

you forget them! |

|

Last

updated 22 Jun 2014 (title layout), 12 May 2007 (text;

first published 4 May

2007)

https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_may2007.html