Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly

Formerly "Picture of the Month"

September-October 2007

The Greening of Pragmatism (III)

(Reflections on Critical Pragmatism, Part 6)

The greening of pragmatism (iii): the way ahead In the two previous parts of this three-part reflection on the "greening of pragmatism" (Ulrich, 2007b and c), we reviewed the emergence of critical pragmatism from the confluence of two major strands of pragmatic thinking – the reformist (or social change) strand of critical pragmatism and the philosophical (or social theory) strand – and briefly considered three basic resources for its methodological development, namely, discourse theory (as understood in critical theory), pragmatic thought (as understood in American pragmatism), and reflective practice (as understood in critical heuristics). In this third and last part, I now propose that we have a look at the next steps ahead, the challenges they pose and the aims that might guide us in facing them. In other words, where do we go from here? However, since it is a while that we have left this discussion, a short glance back may be helpful to begin with.

|

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

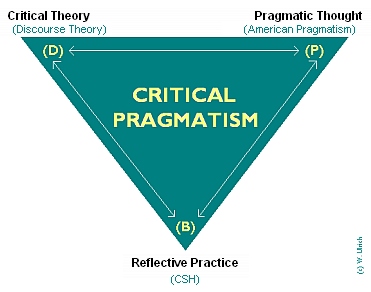

A glance back: critical pragmatism's methodological triangle In the last reflection of this series (in the Bimonthly of May-June 2007) we found that three methodological cornerstones are particularly essential for developing critical pragmatism:

Figure 1: Three methodological cornerstones of critical pragmatism

(D) Discursive principle; (P)

Pragmatic maxim; (B) Principle of boundary critique

[Source:

Ulrich,

2007c, Fig. 1]

The three corners of the triangle stand for three complementary sources of thought on, and methodological advances in, critical pragmatism. With each source I associate a basic methodological principle that I find particularly helpful for developing critical pragmatism, namely: the discursive principle (D); the pragmatic maxim (P); and the principle of boundary critique (B). One of the methodological promises of critical pragmatism for me consists in the fact that by combining them in critical pragmatism, these three principles can support one another and thus may have a better chance to promote critical practice.

However, each of the three sources (or the research traditions from which they emerge) also has its particular difficulties. In fact, none of them can be said to find itself in a particularly healthy state today:

- Critical theory's methodological core concept of rational practical discourse is facing an important deficit of application. In the field of business ethics, for example, critical theorists are suddenly discovering that "discourse ethics" (Habermas, 1990) does not easily lend itself to practical use. A whole new body literature is now emerging about the apparent need to complement discourse ethics, the supposed tool of moral discourse, by some kind of "application discourse" (Günther, 1993), the methodological status of which has remained rather unclear. As far as I can see, critical theorists have not managed as yet to translate the discursive principle into practical tools for securing rational decision making. Their model of communicative rationality, if it is to serve as a guideline for practice rather than a theoretical device only, requires some kind of pragmatic turn.

- Pragmatism has not managed thus far to draw on critical theory with a view to overcoming its methodological deficit in dealing with the normative side of pragmatic reasoning, as little as with the issue of power. The difficulty is, its methodological core principle, the pragmatic maxim, tells us little about handling these issues. In addition, I have in an earlier reflection (Ulrich, 2006c) drawn the reader's attention to the holistic implications of the pragmatic maxim, which render it difficult to practice. Clearly, then, pragmatism's model of practice is calling for some kind of critical turn.

- Finally, the concept of reflective practice has in my view not received a satisfactory treatment. Since Donald Schön (1983, 1987) published his seminal books, a considerable body of literature has developed around this topic and there are even some specialized journals dedicated to it; but unfortunately, this literature has taken a largely subjectivist or psychological turn. "Reflective practitioners" are apparently supposed to deal more with the subjective and emotional aspects of professional intervention than with its rationality, ethics, and the role of power and conflicts. Very clearly, this prevalent notion of what "reflective practice" is all about is calling for both a pragmatic turn (i.e., a new focus on the consequences of professional intervention) and a critical turn (i.e., a stronger focus on the claims to rationality and ethical defensibility that inhere reflective professional practice).

Where do we go from here? The key to overcoming these deficits lies in working together. Where one approach is strong, the others are weaker, and conversely. However, there is one particular difficulty in such a cooperation: the basic assumptions of the three approaches are rather different. Hence, we must ask, does such a cooperation not risk being forced, that is, work against the specific assumptions of each approach? Lest we risk promoting a forced marriage that will not be successful, we better make sure first there are sufficient affinities between the three traditions.

To simplify things a bit, I will focus on the compatibility of critical theory and pragmatism, for in many respects a proper framework for reflective practice (as understood in critical pragmatism) will be grounded theoretically in these two approaches (which is not to say they have a monopoly for grounding reflective practice). The first challenge, then, is to make sure there are sufficient affinities between critical and pragmatist thought to warrant a marriage.

Challenge

#1: Uncovering affinities

between

critical and pragmatist thinking

Perhaps the most central affinity between critical theory (as understood by Habermas) and pragmatism (particularly as understood by Peirce and Dewey) is in their sharing of a discursive conception of rationality. Habermas' (1979, 1984-87, 1990) "language-analytical" or "communicative" turn of critical theory means that the rationality of practice, including that of scientifically supported practice, becomes essentially a question of successful "communicative action," that is, cooperative interaction. Through communicative action we succeed (or fail) to find solutions to problems of mutual concern in a peaceful, argumentative way rather than by resorting to power, manipulation, deception, or other non-argumentative means. Therein consists for Habermas the rational core (or telos) of communication: it aims at mutual understanding, that is, at handling differences of views and interests in a reasonable, cooperative way, supported by institutionalized procedures for debate and democratically legitimate decision making. This focus on cooperative interaction meets with Dewey's (1916, 1927, 1937, ) interest in the deliberative dimension of inquiry and practice, including democratic practice. For him, deliberative practice in as many areas of decision making as possible is indeed the hallmark of an enlightened and democratic society, much more than just reliance on majority rule. In this deliberative conception of rational practice we can certainly see a crucial affinity between critical theory and pragmatism, for it provides a basis for shared methodological efforts.

I see a second affinity, one that may be less obvious. It seems to me that both critical theory and pragmatist philosophy tie their concepts of deliberative rationality to an ideal vision of a society working towards cooperative and consensual problem solutions, that is, mutual understanding. The difficulty with such a vision is that in real-world circumstances of imperfect rationality, cooperation and consensus tend to be scarce resources. As a rule, differences of views and interests cannot easily be bridged by argumentative means. We here encounter a root cause for the relative application deficits of both critical theory and pragmatist philosophy: compared to their strong focus on securing rational (in the case of critical theory) and/or pragmatically clear (in the case of pragmatism) problem solutions, they both suffer from a relative neglect of the crucial problem of problem constitution, that is, of how problems become "problems" that are then subject to solution attempts along either "critical" or "pragmatic" lines or both.

As a way of dealing with this difficulty, my work on critical heuristics stipulates a basic shift of focus, away from the quest for consensus to one for appreciating conflicts of view and understanding the different rationalities of other people; from a conception of rational practice that depends on sufficient justification of validity claims (i.e., complete rationality) to one that only requires sufficient critique, that is, laying open the unavoidable deficits of rationality that characterize any concrete validity claim in a concrete context of inquiry and action. This shift of focus leads to one of the key concepts of critical heuristics, the concept of securing at least a critical solution to the unsolved problem of practical reason, that is, of how in concrete contexts of action we can ever claim to fully justify the normative implications of our problem definitions and solutions.

Once we accept this shift of focus, more affinities between critical theory and pragmatism emerge. For example, both (although in different ways) have abandoned the central concept of Marxist criticism, the concept of "false consciousness." Critical theory replaces it by a discourse-theoretic notion of false consensus, that is, the confusion of merely factual with rational agreement; pragmatism by Peirce's notion of lacking pragmatic clarity, that is, failure to clarify the meaning of our claims with sufficient regard for all their conceivable consequences. Compared to the heavy ideological baggage of the old notion of false consciousness, these two alternative notions share a pragmatic and methodological rather than ideological outlook; yet they have no less critical and emancipatory potential. (It is another question whether and to what extent critical theory and pragmatist philosophy succeed in tapping this critical potential for everyday social practice; the question is important with a view to developing a proper notion of reflective practice.)

In conclusion, I think it is clear from these few reflections that there are indeed a number of methodologically relevant, deep affinities between critical and pragmatist thought.

Challenge #2: Envisioning a philosophy for professionals

We can, then, begin to envisage the kind of philosophical effort that will bring critical theory and pragmatist philosophy closer together. But with what vision in mind should we try to achieve that? It is in this respect that my understanding of critical pragmatism may differ most from that of social science theorists such as Dryzek (1995), White (2004), and others who have dealt (whether explicitly or implicitly) with the idea of a critical pragmatist approach. As far as I can see, they all focus more on the needs of social theory than those of social practice. I do not mean to construct a wrong opposition between the two – I have always emphasized that critical theory of society and critical heuristics of social practice for me are two complementary rather than alternative projects, and that both endeavors require a theoretical (philosophical and methodological) basis – but even so, sound theory does not ensure sound practice (compare the discussions in Ulrich, 2006e and 2007a). The point is the importance we give to the task of supporting not only theorists but also practical people, and with what (more or less ideal or practicable) notion of rational practice in mind we do so.

My vision of where critical pragmatism should take us to is this: it should lead us not only to some kind of pragmatically reconfigured critical theory but towards a philosophy for professionals (Ulrich, 2006d and 2007d). Lest this suggestion should raise mistaken elitist connotations, it should be clear (and I think I have made it sufficiently clear in my writings) that this vision is to be grounded in a notion of professional competence that is emancipatory rather than elitist; that is, it should give ordinary citizens a relevant role to play. One of its underlying motives is in fact to give professionals and citizens the skills they need so that they can meet as equals. An adequate "philosophy for professionals" will thus by inner necessity be a philosophy for professionals and citizens.

Again, this vision of a philosophy for professionals (and citizens) is a complementary rather than an alternative project to "ordinary" (if I may say so) social theory; it is a kind of philosophy that as far as I can see does not yet exist but which will be able to draw on many already existing elements, rather than needing to invent them all from scratch. Its measure of success will consist in its critically heuristic significance for ordinary professionals, decision makers, and citizens, that is, its ability to enhance their skills of critical reflection and argumentation about issues of problem constitution and solution, particularly in controversial situations.

At this point, lest I merely equate critical pragmatism with my previous work on critical heuristics, I would like to call in a second voice, by returning to Stephen White's (2004, p. 311) call for a "pragmatically reconfigured critical theory." In the light of the basic affinities that we have identified above between critical theory and pragmatism, it is hardly surprising that White puts his hopes for achieving a "pragmatist turn" of critical theory on the inherently pragmatist quality of Habermas' notions of communicative action and communicative rationality. Once we recognize this pragmatist quality – and I hope I do not merely project my own notions of critical heuristics and critical pragmatism on White's line of argument1) – we will no longer follow Habermas and burden communicative reason with the role of justifying universal validity claims. This has been the starting point of both my work on critical heuristics (CSH) and my recent attempt (Ulrich, 2006b) to outline a few methodological core conjectures with a view to developing a critical pragmatist framework for ethics.

Furthermore, and this is where White's analysis becomes really interesting and encouraging to me, such a pragmatist reconstruction of critical theory will help us to "see a richer heuristic role for communicative rationality" (White, 2004, p. 320), for example, in examining the role of power in the constitution of research problems or in dealing with particular contexts of action. This is crucial because, as White notes, "judgments about problem resolution are always entangled with the prior issue of problem constitution" (p. 319). Communicative reason thus assumes an essential new role as "a heuristic searchlight upon structures of power" (p. 325).

Indeed! Rarely have I found an account of Habermas' critical theory that would have come closer to the conclusions that I have myself drawn as to how Habermas' work might lend itself to pragmatization, namely, through a critically-heuristic turn of its ideal notion of rational practice (Ulrich 1983, p. 215ff). Whenever cooperative interaction among people becomes problematic due to differences of views or validity claims, Habermas' way of tying the quest for rational practice to argumentatively secured consensus (a consensus that we could claim to satisfy the conditions of the ideal speech situation, such as freedom from oppression, equal access to information, symmetry of argumentative chances and skills, etc.) is difficult to realize. It then becomes vital with a view to maintaining argumentative and cooperative ways of conflict resolution that we succeed in giving communicative reason a more modest yet critical role. In the critical significance of its new "heuristic role," both White and I locate a deeply pragmatic quality of communicative reason – pragmatic in the philosophical (pragmatist) as well as in the everyday (practical) sense of the word, namely, of helping us to achieve mutual understanding about the conditional nature and limited reach of all our claims to rationality and improvement as measured by their consequences. Despite different points of departure and aims, we thus appear to arrive at the same conviction: that it is possible and meaningful to develop a pragmatic and critical paradigm for the social and applied disciplines.

Challenge

#3: Ensuring reflective

practice

in the spirit of critical pragmatism

While I hope that White and other social theorists will pursue the idea of a pragmatically reconfigured critical theory, my own current interest aims more at the two other corners of critical pragmatism's methodological triangle (Figure 1). I believe these two corners stand for equally important elements of critical pragmatism but raise issues different from those of a pragmatist revision of critical theory:

- On the one hand, while a pragmatist revision (and based on it, pragmatization) of critical theory may help us to overcome critical theory's current application deficits, it will not thereby automatically overcome pragmatism's critical deficits in dealing with issues of power and (I would add) ethics. That is, we need to give equal importance to promoting a critical turn of pragmatism and a pragmatist turn of critical theory; only together can they provide a solid (and practicable) framework for the applied disciplines.

- On the other hand, even if both theoretical reconstruction projects – the revision of critical theory and of pragmatist philosophy – can be achieved satisfactorily and within a reasonable delay of time, the job of changing the practice of research and professional intervention will not thereby be achieved automatically. The task of promoting reflective practice is methodologically different from that of revising theoretical conceptions; it challenges us to develop tools of critical reflection and cogent critical argumentation that would be accessible to a majority of ordinary researchers, professionals, decision-makers, and citizens.

This is why in my suggested conception of critical pragmatism, the idea of reflective practice furnishes a vital third cornerstone. In distinction to conventional notions of reflective practice, I understand reflective practice as a mainly philosophical and methodological (rather than psychological) approach to promoting critically reflected practice. The tool of boundary critique – the methodological core principle of my work on critical heuristics – fills an essential gap here (see Ulrich, 2006a, for a first introduction). I believe it provides a key to both the tasks mentioned above, the theoretical task of grounding a critical turn of pragmatist philosophy and the practical task of promoting reflective practice in the spirit of critical pragmatism.

I have elsewhere given an account of my concept of reflective practice (Ulrich, 2000). In a future edition of the Bimonthy, I will look a bit more closely at the way it differs from the currently prevailing concept of reflective practice. Likewise, I will consider the question of how critical pragmatism can help us in grounding reflective practice in a realistic (i.e., applicable) notion of ethical practice – a problem that is apt to furnish a true touchstone for what critical pragmatism can contribute to reflective practice.

Concluding remarks It is obvious that at this stage, critical pragmatism is an open-ended of project. Nobody can safely predict where it will take us to, nobody has a monopoly to define it. It should be clear, however, that unlike what might be said of some variants of contemporary neo-pragmatism, critical pragmatism takes the founding fathers of American pragmatism (Peirce, 1878; James, 1907; Dewey, 1925) seriously. The idea is not to abandon the philosophical project they started but rather, to renew it in the light of contemporary conceptions of discursive rationality, practical philosophy, and reflective practice. Even so, I certainly do not mean to engage in disputes abut what is the "true" form of pragmatist philosophy today. As Susan Haack (2004) has observed,

It is easy to get hung up on the question of which variants qualify as authentic pragmatism; but probably it is better – potentially more fruitful, and appropriately forward-looking – to ask, rather, what we can borrow from the riches of the classical pragmatist tradition, and what we can salvage from the intellectual shipwreck of radical contemporary neo- and neo-neo- pragmatisms. (Haack, 2004, p. 34)

I believe that under present conditions of science and society, of technological civilization and ethical pluralism, of global economic challenges and environmental threats, a critical awakening of pragmatism is in order. The challenge to philosophical pragmatism today is to give pragmatic thought a new methodological significance in supporting research and professional practice as well as everyday problem solving and decision making. Unless we confront this challenge, philosophical pragmatism (or what neo-pragmatism has left of it) may soon be merely of interest to the Times Literary Supplement.

Summary: the greening of pragmatism In three short articles on critical pragmatism's past, present, and future, I have tried to offer some initial conjectures as to how we might recover and develop the methodological significance of pragmatic thought. Can we breathe new life into American pragmatism in general and into the pragmatic maxim in particular? My answer, basically, consists in advocating a critical turn of pragmatist philosophy: I suggest that pragmatism may be most adequately understood as a form of critical thinking, or as "critical pragmatism." As pragmatists we probably think most properly when we think most (self-)critically, that is, when we systematically question our claims with respect to the ends they serve and the consequences they may have, and accordingly qualify and limit them.

Historically speaking, I propose that critical pragmatism is emerging from the confluence of three traditions of thought: American pragmatism, critical social theory, and reflective practice. Methodologically speaking, I propose that we combine the pragmatic maxim (P) of American pragmatism with the discursive principle (D) of critical theory, and these two principles in turn with the principle of boundary critique (B) of critical heuristics. Together, the three principle constitute the methodological core of what I mean by critical pragmatism. I believe there is indeed a deep inner affinity between these three core principles, in that they mutually support and even require each other. None of them is practicable on its own; but together, they may well make a significant difference towards critical practice. It makes sense, then, to think carefully about the ways in which they can support one another and what new conceptions of sound research and professional practice may result from the confluence of the three traditions of thought for which they stand. Let us try and see how far they will carry us.

Note

1) For those readers who are familiar with Habermas' work, I should perhaps point out that in one particular respect, I do not entirely share White's (2004) argument for a pragmatist revision of critical theory, namely, inasmuch as he bases it on the assertion that Habermas is a language foundationalist (p. 117f) and that his communicative turn is tied to a "strong ontological claim about the essence or telos of language" (p. 318). It is of course true that in his early work on a theory of knowledge-constitutive (or cognitive) interests, Habermas (1971) associated communication with an inherent, "anthropologically deap-seated," interest of reason in mutual understanding and rationally motivated consensus (the so-called practical interest of reason); but it is equally true that he has long since modified this early view in favor of an essentially procedural rather than substantive understanding of practical reason. White seems to suggest that only his proposed revision of Habermas' approach to critical social science can overcome Habermas' early foundationalist and ontological claims (or what remains of them) in favor of a basically procedural orientation. Such an account risks missing Habermas' (1979) essential idea of "formal pragmatics," an idea that White does not mention at all but which provided an early constitutive element of Habermas' communicative turn – so early that already in the late 1970s, it influenced my work on "critical systems heuristics" more than the theory of cognitive interests that it replaced (compare Ulrich, 1983, chap. 2). Since then, Habermas has further modified his original conception, particularly in his work on discourse ethics (1990, 1993) and deliberative democracy (1996) and even more so in his recent work on Truth and Justification (Habermas 2005). [BACK]

References

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan.

Dewey, J. (1925). Experience and Nature. La Salle, IL: Open Court.

Dewey, J. (1927). The Public and Its Problems. New York: Henry Holt & Co.

Dewey, J. (1937). Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. Wiley: New York.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Collier Macmillan.

Dryzek, J.S. (1995). Critical theory as a research program. In S.K. White (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Habermas, Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 97-119.

Günther, K. (1993). The Sense of Appropriateness: Application Discourses in Morality and Law. State University of New York Press: Albany, NY.

Haack, S. (2004). Pragmatism, old and new. Contemporary Pragmatism, 1, No. 1, pp. 3-41.

Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and Human Interests. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1979). Communication and the Evolution of Society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, and London: Heinemann.

Habermas, J. (1984-87). The Theory of Communicative Action. 2 vols. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, and Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, Vol. 1: 1984, and Vol. 2: 1987.

Habermas, J. (1990). Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (1993). Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics. Cambridge, UK: UK.

Habermas, J. (1996). Between Facts and Norms. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (2005). Truth and Justification. New edn. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

James, W. (1907). Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. New York: Longman Green & Co.

Peirce, C.S. (1878). How to make our ideas clear. Popular Science Monthly, 12, January, pp. 286-302. Reprinted in C. Hartshorne and P. Weiss (eds), Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vol. V: Pragmatism and Pragmaticism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934, para. 388-410, pp. 248-271.

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland: Haupt. Reprint edn. Chichester, UK, and New York: Wiley, 1994.

Ulrich, W. (2000). Reflective practice in the civil society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268

Ulrich, W. (2006a). The art of boundary crossing. Ulrich's Bimonthly (formerly Picture of the Month), May 2006. http://wulrich.com/picture_may2006.html .

Ulrich, W. (2006b). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional and business ethics. In L. Zsolnai (ed.), Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business Ethics, Vol. I. Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, and Bern, Switzerland, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich, W. (2006c). A

plea for critical pragmatism. (Reflections

on critical pragmatism, Part 1). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, September-October 2006.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2006.html .

Ulrich,

W. (2006d). Rethinking

critically reflective research practice: beyond Popper's critical

rationalism. Journal of Research

Practice, 2, No. 2 (October), article P1.

[HTML] http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/64/63

.

Ulrich,

W. (2006e). Theory and practice I: beyond theory. (Reflections

on critical pragmatism, Part 2). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, November-December 2006.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2006.html .

Ulrich,

W. (2007a). Theory

and practice II: the rise and fall of the "primacy of theory."

(Reflections on critical pragmatism, Part 3). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, January-February 2007.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_january2007.html .

Ulrich,

W. (2007b). The greening of pragmatism

(i): the emergence of critical pragmatism. (Reflections on critical pragmatism, Part 4). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, March-April 2007.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2007.html .

Ulrich,

W. (2007c). The greening of pragmatism (ii): current

issues in developing critical pragmatism

– a methodological trilemma. (Reflections on critical pragmatism, Part 5). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, May-June 2007.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_may2007.html .

Ulrich, W. (2007d). Philosophy for professionals: towards critical pragmatism. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 58, No. 8, pp. 1109-1113.

White, S.K. (2004). The very idea of a critical social science: a pragmatist turn. In F. Rush (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 310-335.

|

September 2007 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

October 2007 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Picture data Digital photograph taken on 6 July 2007 at 7:45 p.m. near Koniz (Bern). ISO 50, aperture f/4.0, shutter speed 1/500, focal length 9.6 mm, equivalent to 47 mm with a conventional 35 mm camera (i.e., full-format sensor). Original resolution 2272 x 1704 pixels; current resolution 700 x 525 pixels, compressed to 110 KB.

The way ahead for critical pragmatism: Uncovering affinities between critical and pragmatist thinking – Envisioning a philosophy for professionals – Ensuring reflective practice

(Three challenges discussed in this reflection on critical pragmatism)

Notepad for capturing personal thoughts »

|

Personal notes:

Write

down your thoughts before

you forget them! |

|

Last updated 22 Jun 2016 (two

typos corrected), 3 Sep 2007 (text; first published 1 Sep

2007)

https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2007.html