|

|

|

An

"Eastern" perspective: three ancient Indian ideas

(continued)

In the previous essay, we familiarized

ourselves with the world of ideas of the Vedic tradition of

ancient Indian philosophy and particularly with the Upanishads.

The present second essay focuses on three concepts that play an

important role in the Upanishads and also appear particularly

interesting from a methodological point of view:

brahman,

atman, and jagat. Like earlier essays in this series,

this one and its sequels are again structured into "Intermediate Reflections,"

to emphasize the exploratory character of the considerations

in question. The first

of these (and sixth overall), which makes up the present essay, analyzes the

meaning of the three concepts as they are employed in the Upanishads. A

subsequent reflection, which will be offered in the next Bimonthly, will

discuss a specific example in the form of one of the most famous verses of the

Upanishads. Two later reflections, planned for the final part of the series,

will be dedicated to a complementary, language-analytical view of the

Upanishads and to the question of what we can learn from Upanishadic thought, and

particularly from the three core ideas we analyzed, about the proper use of

general ideas today.

Sixth

intermediate reflection:

Three essential ideas of ancient

Indian thought

A caveat Before we

consider the etymology and meaning of the three concepts of

brahman, atman, and jagat, a word of caution is in order. Being

thoroughly grounded in a Western, Kantian tradition of thought,

I do not assume that with some fragmentary (though careful) reading of

English translations of ancient Indian texts, combined with

some introductory accounts and commentaries, it is possible to gain a

sufficient understanding

of the entirely different tradition of thought in which they originate,

the Vedic tradition. I accept

the cautionary words of Müller (1879), who in the Preface

to his translation of the Upanishads notes that there are three basic obstacles

to understanding these ancient "sacred texts of the East,"

as he calls them, from a modern Western perspective:

I

must begin this series of translations of the Sacred Books of the East

with three cautions:--the first, referring to the character of the

original texts here translated; the second, with regard to the

difficulties in making a proper use of translations; the third, showing

what is possible and what is impossible in rendering ancient thought

into modern speech.

(Müller, 1879, p. ix) In

short, we must never forget that deep-seated differences of

culture, language, and epoch create a distance to these ancient

texts that is difficult to overcome, certainly for a Western

mind. As a result of all three difficulties, particularly the

first, Müller notes that the Upanishads,

along with their bright and illuminating

sides, also have their "dark"

(1879, p. xi)

and at times "almost unintelligible"

(1879, p. xiv)

sides. They can tell us much about "the dawn of religious

consciousness of

man," something that "must always remain one of the most inspiring and hallowing sights

in the whole history of the world" (1879, p. xi); but there is also

"much that is strange and startling, … tedious … or repulsive, or, lastly, …

difficult to construe and to understand." (1879, p. xii)

If an eminent scholar like Müller feels compelled to avow of

such difficulties and limitations in studying the Upanishads,

it should be clear from the outset (and I want to leave no doubts)

that my reading of some of these texts can only provide

a very limited understanding; limited, that is, by my current

interest in the role of general ideas within the Western tradition

of rational ethics. My interest is a methodological rather than

a metaphysical one, much less a religious one. The aim is to

develop the notion of a "critically contextualist"

handling of general ideas, and it is

within this context that what I'll say about the three Upanishadic

concepts of "brahman," "atman," and "jagat"

should be

understood and used. For once, the (limited) end of my

undertaking hopefully justifies the (equally limited) means.

With this cautionary

remark in mind, let us now turn to the three selected concepts.

Three

essential Upanishadic ideas: brahman,

atman, and

jagat

"Brahman" The major theme of all Vedanta texts

and particularly of the Upanishads is the human

endeavor of seeking knowledge of brahman, the ultimate, unchanging,

and infinite

reality that lies beyond all limitations of the phenomenal world,

although it also manifests itself in it as well as in the human

individual's innermost consciousness and spirituality, the "self."

Brahman

thus embodies the notion of both a transcendent and

an immanent reality. As a transcendent reality, its essence

is prior to and "beyond all distinctions or forms" (Easwaran, 2007,

p. 339); accordingly we cannot grasp it in our perceptions and

descriptions of the world. As an immanent

reality, it nevertheless permeates or, as the Upanishads

put it, “dwells in” these perceptions and descriptions; accordingly we cannot properly understand what they

mean unless we understand them as imperfect and fragmentary expressions of that other, larger or higher reality that is not

accessible to us in any direct and objective way.

In the more analytical terms

used earlier, we might also understand brahman to embody the universe

of second-order knowledge, the conceptual tools and efforts without

which we cannot adequately understand our first-order knowledge,

that is, more accurately, the manifold particular universes within which the individual’s perceptions,

thoughts, and actions move at any time. Among such second-order devices I would count the main subject

of this series of essays, general ideas and principles of reason,

along

with categories of knowable things, modalities of meaningful statements, forms of valid inferences or arguments, and other

concepts that enable us to think and talk clearly about our

first-order knowledge and its limitations.

Root

meanings The word “brahman” (from the Sanskrit root brh-, "to swell, expand, grow, increase") is basically

a neuter noun that stands for an abstract concept of the universe – the ground of all being – rather than for a

personification of its divine originator. However, the latter interpretation

can also be found (e.g., in the Isha Upanishad) and the word can then, as in a few

other specific meanings, take the masculine gender. In between an entirely

impersonal and a personified notion lies a third frequent understanding of

brahman, as the one universal spirit or soul that is thought to inhere the

entire universe and thus also the human spirit. Forth and finally, since there

is no sharp distinction between the knowledge that an enlightened person is

seeking to acquire and the sources of such knowledge, the term brahman can also

be found historically to stand for the sacred texts or, in the previous oral

tradition, the sacred words that reveal the knowledge in question. If there is

a common denominator of these various, partly metaphysical and partly religious

meanings, we might see it in the notion that brahman is always that which needs

to be studied on the path to enlightenment – yet another

reference to second-order

knowledge, in the analytical terms adopted in the previous essay.

This is obviously

a highly simplified account of the etymology of the brahman

concept, given that the major Sanskrit-English

dictionary of Monier-Williams (1899, p. 737f, and 1872, pp.

689 and 692f; cf. Cologne Project, 1997/2008

and 2013/14, also

Monier-Williams et al., 2008) lists no less than some 27 meanings of brahman.

Table 1 offers a selection and also highlights some of the

meanings of most interest here.

|

Table 1: Selected meanings of

brahman

(Source: Monier-Williams, 1899, 737f

and 741, and 1872, pp.

689, 692f, abridged and simplified) |

|

brahman, bráhman, n[euter

gender]. brahman, bráhman, n[euter

gender].

(lit. "growth," "expansion,"

"evolution," "development," "swelling of

the spirit or soul") pious effusion or utterance, outpouring of the heart in

worshipping the gods, prayer.

|

|

the sacred word

(as opp. to vac, the word of man), the veda, a sacred text, a text or

mantra used as a spell [read: magic formula]; the sacred syllable Om. |

|

the brAhmaNa portion of the veda.

|

|

religious or spiritual

knowledge (opp. to religious observances and bodily mortification such as

tapas). |

|

holy life (esp. continence, chastity; cf.

brahma-carya). |

|

(exceptionally treated as m.) the brahma or [the]

one self-existent

impersonal Spirit,

the one

universal Soul (or one divine essence and source from which all created things

emanate or with which they are identified and to which they return), the

Self-existent, the Absolute, the Eternal (not generally an object of worship,

but rather of meditation and knowledge). |

|

bráhman,

n[euter gender]. the class of men who are the

repositories and communicators of sacred knowledge, the Brahmanical caste as a

body (rarely an individual Brahman). |

|

wealth;

final emancipation.

|

|

brahmán,

m[asculine gender].

one who prays, a devout or

religious man, a Bráhman who is a knower of Vedic texts or spells, one versed in

sacred knowledge. |

|

the

intellect

(=buddhi). |

|

one of the four principal priests or ritvijas; the brahman was the

most learned of them and was required to know the three vedas, to supervise the

sacrifice and to set right mistakes; at a later period his functions were based

especially on the atharva-veda). |

|

brahmA, m[asculine

gender]. the one impersonal universal Spirit manifested as a personal Creator and as the first of the triad of personal gods

(he never appears to have become an object of general worship, though he has two temples in India). |

|

brAhma, n[eutral

gender]. the one self-existent Spirit, the Absolute. |

|

sacred

study, the study

of the Vedas. |

|

brAhma, m[asculine

gender]. a priest. |

|

brAhma, mf

[masculine or feminine gender]. relating to sacred

knowledge, prescribed by the Vedas, scriptural;

sacred to the Vedas; relating or belonging to the brahmans or the sacerdotal class. |

|

brahmin, mfn

[masculine, feminine or neutral gender]. belonging or relating to brahman or brahmA;

possessing sacred knowledge. |

|

Copyleft  2014 W.

Ulrich 2014 W.

Ulrich |

Derived

meanings The neuter noun brahman should not be confused with its masculine versions,

which are also written "brahmin" and "Brahmana."

A

brahmin or a brahmán (as a masculine noun) is

"a

knower of Vedic texts" (Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 738;

Macdonnell, 1929, p. 193); a devout man, priest or spiritual teacher

(guru) "versed in sacred texts" (1872, p. 689);

a seeker on the

path to knowledge of brahman (brahmavidya) who usually is also a member of the brahmanic

caste. The term can also stand for

the caste itself, as "the class of men who are the

repositories and communicators of sacred knowledge" (1899, p. 738),

in which case it is used in the neuter gender.

Further,

the noun brahma (except as part of compounds) should be distinguished from brahman; in the neuter

gender it stands for a personification of brahman that is conceived in a rather abstract

way, as a universal consciousness or "universal spirit" that manifests

itself in the world and in the human individual. There are also

a number of derivative meanings (partly used in composite terms

such as bramavidya or bramacarya, the study and

practice of brahmanic knowledge) in which the term often takes

the masculine or (rarely) the feminine gender and designates

either the "sacred knowledge" of the Vedas or the

person who possesses it. In contemporary, post-Vedic (and thus also

post-Vedantic) Hindu religion, finally, brahma is now often also understood

as referring to a personal creator-God and as such is worshipped

as the main god in the divine trinity (or trimurti) of

Brahma,

Vishnu, and Shiva, an understanding that is not, however,

characteristic of Upanishadic thought.

Personal reading The concept of primary interest to

us is the abstract, impersonal

notion of brahman as an invisible reality that lies

beyond, yet informs, all we can perceive and say about the world, a "source from which all created things emanate"

(Monier-Williams, 1899, p.

737, similarly 1872, p. 689) and which accordingly we would need to understand so as to ensure

reliable

knowledge and proper action. Navlakha (2000) nicely summarizes this non-religious,

philosophical understanding:

Brahman

as the absolute reality is purely impersonal, and is not to

be confused with a personal God. The significance of brahman

is metaphysical, not theological. Brahman is the featureless

absolute, which unless a contextual necessity otherwise demands,

is most appropriately referred to as 'It'. [Which is to say,

the] brahman of the Upanishads is also not to be seen

as the Creator God, as in Judaeo-Christian tradition. There

is no creation as such in Vedanta. The universe is evolved out

of brahman. [… ] Thus brahman is the one and only

cause of the coming into existence of the universe. Brahman

is whole and unfolds itself out in the form of the universe,

out of its own substance, and as a means of knowing itself.

[…]

Thus there is nothing, not even the minutest part of the material

world, that is not wholly brahman. Within and without,

it is all brahman. (Navlakha, 2000, p. xviiif)

For

our present purpose, I take it indeed that "the significance

of brahman is "metaphysical, not theological." It

is the notion of a "universe"

that lies both

"within and without" our awareness of the world. We cannot grasp it in any direct way, but

it informs

our personal world and at the same time takes us beyond it. This universe is "whole"

in that no-one (whether a religious believer or not) can claim

to stand outside of it, and "featureless" in that whatever ideas we make ourselves

of it, they are our own constructions rather than being objectively given.

It is a deeply metaphysical (and thus not unproblematic) notion, but one we cannot easily

dispense with altogether. Such

appreciation on the part of a Kantian thinker for a metaphysical

notion may appear surprising at first glance; but the

point is of course that I share Navlakha's plea for a metaphysical

rather than just religious understanding. As we said

earlier, what matters is not that we avoid metaphysics (an impossible

feat) but how we handle it. Well-understood metaphysics

invites critique. This becomes clear as soon as we understand

the phrase "all created things" to include

our individual and social constructions of reality, our propositions about, and actions in, this world of ours,

along with the ideational universe that informs them. The

critique required then includes methodological reflection –

reflection, that is, about what "really" is to count

as true knowledge and rational action and for what reasons, in general

(theoretically) as well as in specific contexts of thought and

action (practically).

In this respect, parallels

may well be drawn between Upanishadic and Kantian thought. Neither

can do without metaphysical assumptions; both lend themselves

to epistemological and methodological

considerations that are far from being irrelevant to our epoch, in

that they are apt to question prevailing conceptions of knowledge and

rationality. I

will discuss two examples in a moment, concerning the unsatisfactory ways in

which these conceptions deal with the issues of holism and of subjectivity;

but first it may be useful to briefly consider how metaphysical

assumptions can give rise to methodological reflection.

Metaphysics

and methodology From

a methodological point of view, there are some particularly

interesting parallels here between

Kant's

concepts of pure reason and a non-religious

concept of brahman. In both cases we face ideas

that exceed the reach

of ordinary human knowledge and insofar are bound to remain problematic;

at the same time, again in both cases, we recognize that reasonable thought cannot

do without some ideas of this kind. Both can therefore

also provide impetus for a more than merely superficial

critique of knowledge. For example, as we found in our earlier discussion of Kant's

understanding of general ideas (see Ulrich, 2014a, "Third

intermediate reflection"), we cannot think of a series

of conditions that would explain any specific phenomenon of

interest, without also thinking

of an ultimate, unconditioned condition. As Kant (1787, B444)

puts

it, "for a given

conditioned, the whole series of conditions subordinated to

each other is likewise given"; but that "whole series"

(i.e., totality) of conditions is itself unconditioned, as otherwise

it would depend on some further condition and thus could not

furnish a complete explanation (cf. 1787, B379, B383f, B444 and B445n). In

short, explanations that really explain anything will always

reach beyond the experiential world of conditioned phenomena.

Of necessity they include general ideas that refer us to some

unconditioned whole of conditions, which is what Kant means

by pure concepts of reason. "Concepts of reason contain the unconditioned."

(1787, B367). Likewise, in the Upanishads, when brahman is

said to stand for the "ground of all being" or "source from which all created things

emanate" (Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 738), or is described as the "one,"

"ultimate" and "absolute" (i.e., unconditioned)

reality that lies behind people's multiple realities, such a

notion amounts no less to an unavoidable

idea of reason than does Kant's notion of a totality of conditions

that is itself unconditioned.

Metaphysics

and methodology are close sibilings here. The methodological significance

of brahman for the practice of reason shines through in many metaphysical

characterizations, both in the Upanishads themselves and in

the secondary literature. As an illustration from the Upanishads,

there is this famous prayer in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

in which the devotee seeks guidance on the search for reality

and self-realization:

Lead

me from the unreal to the real!

Lead me from darkness to

light!

Lead me from death to immortality!

(Brihadaranyaka

Upanishad, 1.3.28, as transl. by Müller and Navlakha, 2000,

p. 76, similarly Olivelle, 1996, p. 12f)

That

is to say, truth is not of this world; reality is not to be

found in the phenomenal world. Our human "real world"

is deceptive, a source of darkness rather than light. It obscures

rather than illuminates that basic source of insight that is

called brahman and which is the only reliable source of orientation

for proper thought and action.

This

Upanishadic explanation of the real world's deceptiveness is

metaphysical, but not therefore methodologically irrelevant.

In fact, its methodological implications are largely equivalent

to those of Kant's similar conception of a noumenal (i.e.,

intelligible, ideational) world as distinguished from the phenomenal

(observable, experiential) world. Both pairs of concepts are

about our notion of reality, that is, they rely on metaphysical

assumptions that obviously remain open to challenge. Both frameworks

also handle their assumptions in a critically self-reflective

fashion; neither claims that the metaphysical is knowable. Rather,

the metaphysical assumptions in question function as calls to

a discipline of critical self-reflection on the part of the

knowing subject. They represent critical reminders, not presumptions

of knowledge. Interestingly, the two frameworks share this critical

orientation although they differ in the ways they understand

and handle their metaphysical underpinnings: while for

the Upanishadic thinkers, brahman is a symbol of the objective

world that is ineffable but real, as opposed to the world's

deceptiveness, Kant's Critique does not of course permit

any reification of the noumenal world; he understands it as

a transcendental (i.e., methodological) rather than transcendent

(i.e., metaphysical) concept. Kant thus puts the relationship

of the noumenal (metaphysical) and the phenomenal (experiential)

– of "that" and "this" world – on its head:

it is not the abolute and universal (and for some, the esoteric)

but the empirical and particular (the exoteric) which for Kant

constitutes "reality." Still, the methodological challenge

remains: for Kant, too, there is no such thing as a direct

access to reality, for the empirical is always already infomred

by our cognitive apparatus or, in Kant's more precise terms,

by reasons's a priori categories and ideas. Both

frameworks, then, live up to the demand of reason that we formulated

above: "well-understood metaphysics

invites critique."

As

a second illustration, this time from the secondary literature,

let us consider one of those many descriptions of brahman that

are reminiscent of Kant's recognition of the unavoidability

of the idea of a totality of conditions that is itself unconditioned

(the basic principle of reason). In his Fundamentals of Indian

Philosophy, Puligandla (1977, p. 222) describes brahman as an "unchanging reality amidst and beyond the world"

(my italics). The "amidst" is apt to remind us that whenever we try to explain some

real-world phenomena, we have always already presupposed

that there is a complete series of conditions – perhaps also

some fundamental, unifying force

or principle – that would indeed allow

us to explain the conditioned

nature of things the ways we customarily do it and rely upon, whether in science

or philosophy, in everyday argumentation or practical action. Whether such a

reliable, sufficient ground of explanation exists indeed and how it would

have to

be defined and proven (i.e., explained, an impossibility by

definition), we ultimately have no way to tell. But then again,

methodology, unlike metaphysics, can do without pretending such metaphysical

knowledge. It is quite sufficient for methodological purposes

to recognize that what we can know empirically (the phenomenal

world) is not identical with reality and conversely, that the

real lies at least partly beyond the phenomenal and therefore

also beyond knowledge. Recognizing a lack of knowledge can be a basis

for compelling methodological reflections and conclusions.

Neither in Upanishadic nor in Kantian thought

we depend on an ontological proof of some last conditions

to deal appropriately with the conditioned nature of all we

can observe, think, and claim to know. What matters is to recognize that without assuming

(which is not the same as proving) a whole series of conditions

that is complete, we cannot think

and talk clearly about our knowledge of the world and its limitations.

But since at the same time we can never demonstrate the reality

of a sufficient set of conditions, our practices of inquiry

and argumentation have to learn to handle the situation accordingly

and to be careful about their claims and ways of supporting

them. The Upanishadic way of envisioning such

an assumed, sufficient set of conditions is brahman,

and its way of handling the situation is by "seeking to

know brahman" – or, to put it more carefully, by seeking

to get closer to knowing brahman – for instance, through

meditative and mystical means; through a discipline of self-reflection

and self-limitation; and ultimately through one's entire practice

of life.

As

is to be expected in view of brahman's ineffable

nature, the Upanishads and their commentators suggest many different descriptions of it.

Still, if we are to believe the Encyclopaedia Britannica,

"they concur in the definition of brahman as eternal, conscious, irreducible, infinite, omnipresent, spiritual source of the universe of finiteness and change."

(Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2013b) In the light of what we just

said, such a definition must look excessively metaphysical. To

do justice to the Encyclopaedia, it mirrors the language of the Upanishads and

of most commentators. No faithful account of the Upanishads can entirely avoid explaining them

in their own terms, so readers will also find some metaphysical language

in my continuing account. As the discussion thus far should

have illustrated, this circumstance need not stop us from focusing on methodological considerations.

Unlike metaphysical considerations, which are about the nature

of reality (i.e., ontology), the core concern of methodological

questioning as I understand it is the proper use of reason for achieving

practical or theoretical ends (i.e., rationality). Instead of complaining about the metaphysical character

of the Upanishads, we can make a difference by analyzing what

they have to tell us about the proper use of reason. Why not

try to do this from a critical, contemporary perspective, while still trying to remain

faithful to the language, spirit and wisdom of these ancient texts?

The proper use of reason and the quest for practical excellence

The

proposed methodological interest

in the Upanishads is quite compatible, I think, with their

essential orientation towards the practical: in Upanishadic thought, the study of brahman

matters as much for mastering our lives as for purely speculative reasons. Remember

what we said in the introductory essay about the importance

of concepts

such as svadharma (one's individual

dharma or "law) and karma (from karman = work, action, performance;

one's record of good deeds which is effective as cause

of one's future fate). Their essential, practical concern is

to guide us in developing right thought and conduct

on the path to individual self-realization. Similar observations

could be made about the implications of such concepts for professional

self-realization, for example, by cultivating high standards

of excellence in one's practices of inquiry, consultancy, and

other uses of professional expertise. The quest for practical excellence

requires no less an effort of self-reflection and self-limitation, along with

clear and consistent reasoning, than does the search

for theoretical understanding.

As always, such demands

are easier formulated than put into practice. In practice, they

face us with considerable difficulties. Specifically, as we

have emphasized with reference to Kant, the proper use of reason

depends on considering all the circumstances

that might be relevant, not just those that present themselves immediately

and/or conform to our private interests. Whether for practical or theoretical ends –

a distinction

that the Upanishads do not draw as sharply as we tend to do

it nowadays – the need for maintaining the integrity of reason

entails a need for comprehensiveness with respect to the conditions

or circumstances we take into account. Any

other kind of account of situations and what might be done about

them is not only potentially deceptive but also arbitrary, in

that it relies on selections of relevant circumstances that

remain unconsidered, if not undeclared and unsubstantiated.

On the other hand, complete rationality

is obviously beyond our capabilities, both in thought and in action. We are well advised to strive for it,

but not to claim it. This is the basic philosophical dilemma with which the Upanishadic demand

of "seeking to know brahman" confronts us: the simultaneous need for,

and unavailability of, an objective and comprehensive grasp

of reality beyond the ways it manifests itself to us or interests

us privately, whether in everyday life or in situations of professional

intervention. In Upanishadic terms, to understand this world of ours we must also strive

to comprehend that other world which lies beyond it but is part of the total

reality.

The better one understands this dilemma involved in the proper use of reason,

and thus also in the search for practical excellence, the more one will appreciate the often

mystic and poetic (rather than strictly philosophical) approach of the Upanishads. To understand our daily world of experience and action, they tell us, we need to

develop a discipline

of seeking distance (the discipline involved in seeking

to know brahman). Distance, that is, from our usual ways of being

situated in the world, which prevent us from seeing "situations" (i.e.,

individual or collective situatedness) as

clearly and objectively as proper thought and action would require. What at

first glance may look like an escape – a mere way of avoiding a philosophical

difficulty – then becomes understandable as a methodically pertinent response: its point is practicing detachment from the world as it is apparently given, or

from situations as they present themselves to us and raise in us egocentric and short-sighted

concerns about them. Thus understood, the mystic and poetic-metaphysical language of the Upanishads carries a deeply philosophical message

indeed. In essence, though perhaps not always in formulation and elaboration, this

message is akin to that of Kant: knowledge, unless it is subject to the

proper use of reason, is as much a source of error as it is a source of

certainty.20)

The

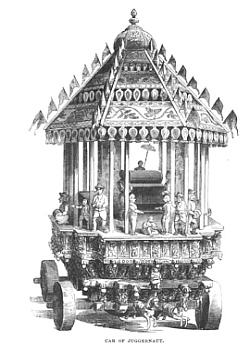

problem of holism One

of the traditional ways of framing the dilemma in Western philosophy

is in terms of the problem of holism. Whatever we know,

think, and say about the world, it is insufficient as measured

by the latter's holistic nature. This methodological implication comes to the fore in

the beautiful, at first rather mystical Invocation (i.e.,

an incantation, the chanting of magical words or formulas at

the outset of a prayer or meditation) that introduces

several of the Upanishads that belong to the Yajur

Veda, among them the Brihadaranyaka, Isha, and Shvetashvatara

Upanishads. I cite their identical invocation here, first in

Sanskrit and then in three

slightly different translations, all of which are customary in the literature.

Note again the previously discussed, careful use of the terms

"this" and "that" in all three versions: I cite their identical invocation here, first in

Sanskrit and then in three

slightly different translations, all of which are customary in the literature.

Note again the previously discussed, careful use of the terms

"this" and "that" in all three versions:

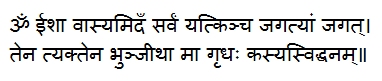

om

purnamadah purnamidam purnaat purnamudachyate

purnasya purnaamadaya purnameva vashishyate

om shanti shanti shanti

(Source:

Swami J. [n.d.], http://www.swamij.com/upanishad-isha-purna.htm

The

key word purna is the perfect participle of the verb

pur, which appears to be related to the English verb

"to pour" and means as much as "poured out,"

"filled" or "full," and hence "complete,"

"whole," "entire," and more figuratively

also "accomplished," "contented," "powerful,"

and so on (see Apte,

1890/2014, p. 715, and 1965/2008, pp. 14 and 139). In the

following translations of the invocation, the initial and final

magical words 'om' and 'shanti' are not repeated:

All

this is full. All that is full.

From fullness, fullness comes.

When

fullness

is taken from fullness, fullness still remains.”

(Invocations

to the Isha, Brihadaranyaka and Shvetashvatara Upanishads, as transl. by Easwaran, 2007, pp. 56, 93,

and 158; similarly transl. by Nikhilananda, 1949, p. 200,

and 2003, pp. 86 and 254; note that in the Sanskrit text, "all

that" comes before "all this," as is the case

in the following translations)

That is whole,

this is whole.

This whole proceeds from that whole.

On taking

away this whole from that whole, it remains whole.

(Invocation

to the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, as transl. by Müller/Navlakha,

2000, p. xix)

That is infinite, this is infinite;

From that infinite this infinite comes.

From that infinite, this infinite removed or added,

infinite remains infinite.

(Invocation to the Isha Upanishad,

as cited, along with a selection of other customary translations,

in the Yoga site of Swami J [n.d.].)

Indeed,

in view of the infinite and transcendent nature of "that"

world of brahman, which nevertheless inheres and conditions

"this" finite but infinitely variable world of of ours,

need we not wonder how we may claim to understand

anything without understanding the ways in which it relates

to that larger, full reality of which it is a part?

As both the Upanishads and Kant's ideas of reason make us understand,

human reason needs

this holistic notion of an all-inclusive whole as a reference point in relation to which it can situate

its own perennially conditioned nature, its amounting to so

much less than a comprehensive and objective grasp of things.

At

the same time, any such notion is bound to remain

a problematic idea of reason. Holistic

knowledge and understanding is a claim that cannot be redeemed argumentatively,

whether based on logic or empirical inquiry or both. Logic tells us that we need it, but not

what it is; and inquiry fails as the whole

reaches beyond the empirical.

The

Upanishadic thinkers understood this dilemma very clearly, some

two and a half thousand years ago, before the disciplines of

logic and epistemology were available to them. Their way

of putting it was metaphysical and metaphorical, by means of

the

two great Upanishadic symbols (or metaphors) of human striving, atman, as

the embodiment of individual self-knowledge and self-realization

(a concept to which we will

turn a little latert), and brahman as the embodiment of proper

universal knowledge, that is, understanding of the

unity and perfection of the universe. Expressed in these terms,

the problem of holism consists in the difficulty that atman cannot find brahman empirically in

"this" world, through

the means of inquiry, nor logically, through the means of inference. For

the whole is not only beyond the empirical, it is also, as the

Upanishads teach us, "one

without a second," that is, unique

(Chandogya,

6.2.1-2) and therefore beyond logic. There is no logic

of uniqueness, no stringent inference

from what we know empirically (i.e., particulars) to what is unique

(i.e., universals). Both epistemologically

and analytically, the universal lies beyond human knowledge.

Still, reason cannot do without the notion of universal qualities

and principles. It cannot renounce the quest for a full understanding

of reality in such terms. Human striving for knowledge of brahman

is therefore a meaningful and indispensable quest, although

we should

never assume that we have actually achieved it.

This,

then, is the Upanishadic way of describing the methodological

dilemma with which the problem of holism confronts us. To this

day it has remained a classical dilemma

in many fields of philosophy such as language analysis and semiotics,

hermeneutics, epistemology, and practical philosophy, and also in

my work on critical systems

heuristics (CSH). In the terms of the Upanishads: atman needs to seek knowledge

of brahman and yet must avoid any presumption of knowledge.

Or, as I like to put it in the terms of CSH:

"Holistic thinking – the quest

for comprehensiveness – is a meaningful effort but not

a meaningful claim." (Ulrich, 2012a, p. 1236;

similarly in 2012b, p. 1314 and, as applied to the moral

idea, in 2013a, p. 38) This situation has motivated my call for a “critical turn” of the

contemporary understanding of competent inquiry and rational practice.

The essential aim then becomes ensuring sufficient critique

rather than sufficient justification of theoretical or practical

claims. This is feasible because, as we said above, recognizing a lack of knowledge can be a basis

for compelling methodological provisions. The methodological consequence is a need for what I call a “critical systems approach” to research and

professional practice, that is, a framework that would provide methodological

support to critically comprehensive thinking or, as I originally

defined it in CSH, an approach that aims to "secure at least a critical

solution to the problem of practical reason" (Ulrich, 1983, pp. 25, 34-37, 177, and passim).

The

problem (and richness) of subjectivity A second methodological implication of the metaphysical

concept of brahman concerns the importance of subjectivity. Once we have

understood that human thought cannot do without assuming some

ultimate,

unconditional ground of all that exits – a totality of conditions

that exists in an unconditional,

absolute, perhaps objective way – we also begin to understand

how limited and subjective all our perceptions of this world

of ours are bound to be, amounting at best to glimpses of that

underlying larger, infinite reality. It follows that whatever knowledge of things we can aspire to

possess, it will be

so much less than objective, as it can just grasp aspects of

that which is "really" the case. The objective is elusive, for it would be all-inclusive.

Ganeri (2001, p. 1) succinctly

speaks of brahman as "the Upanishadic symbol for objectivity itself,"

as opposed to "the subjectivity that goes along with being situated

in the world." As the Mundaka

Upanishad puts it, brahman stands for that all-encompassing,

infinite reality in which everything else is rooted and "through which,

if it is known, everything else becomes known" (Mundaka

Upanishad, 1.1.3, as transl: by Müller, 1897/2000, p. 47,

and Müller/Navlakha, 2000, p. xi; note that the latter

source wrongly refers to Mundaka 1.1.4). As I would

put it, the Upanishads can inspire in us the humility of accepting

that there are limits to what we can hope to know and understand,

due to our being situated in this world. Such awareness

can encourage mutual tolerance, as well as reflective practice

in the sense of paying attention to the ways in which people's

individual situatedness may shape their views and values. Multiple,

differing views also embody a richness of views that would not

be attainable otherwise, and thus have intrinsic value in the

quest for comprehensiveness, for seeking to better know brahman.

Methodologically speaking,

then, the situation is not quite as bad as it looks

metaphysically. Although there are always limits to what as

individuals we can claim to know,

no specific limits are beyond questioning and expansion;

and to this end, we can always listen and talk to others.

In

the Upanishadic conception of inquiry, brahman furnishes the

standard for such questioning. As the Upanishads admonish us time and

again, we can "really" know and

understand things only inasmuch as we know and understand them

in their relation to brahman. Brahman, in the metaphysical terms

of the Upanishads,

is the conception of a reality that, because it is "self-existent"

(Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 737f),

is independent of any condition external to it. It thus mirrors, in

our own discourse-theoretical terms,

the ideal of a self-contained account of reality that could

do without any reference to conditions

outside its own universe of discourse and thus would be entirely

true and reliable. As an ideal, it does not lend itself to realization;

but it certainly provides impetus for critical thought – about

the ways our accounts of reality fail to be self-contained

and, worse, about our usual failure to limit our claims accordingly.

This is a conception of knowledge that is important indeed for our understanding of general ideas of reason. The

parallels we encountered earlier between the Upanishadic concept of brahman as an absolute,

all-inclusive, and infinite reality on the one hand, and Kant's concept of a totality of

conditions (or an infinite series of conditions) that reason cannot help but

presuppose on the other hand, are relevant here. Both concepts

confront us with unavoidable limitations of human knowledge.

Both therefore also imply the need for a discipline of self-reflection and self-limitation. But

of course, there is also an important difference, in that the two traditions of

thought have developed this discipline in entirely different directions – meditative

spirituality and ascetism in the one tradition, critique of reason in the other.

The deeper, underlying difference is that Kant makes us understand the totality

of conditions as a methodological rather than metaphysical concept or, in his

terms, as a transcendental rather than transcendent idea. Although a

conventional, metaphysical and spiritual reading may well remain

of primary importance to most people in studying the Upanishads, the mentioned

parallels nevertheless suggest to

me that a metaphysical reading can and should lead on to a critical

study of what these ancient texts have to tell us about present-day

notions of knowledge, science, and rationality, as well as about

the roles we give these notions in modern societies. For example,

such a reading might encourage a critique of science

that reaches deeper than current notions of reflective practice

in science and professional practice. Such critique in turn

might provide new impetus for the necessary discourse on how contemporary

conceptions of science-theory, research philosophy, theory of knowledge, and practical

philosophy could be developed so as to overcome the crisis of rationality to which I briefly

referred

at the outset (Ulrich, 2013c, p. 1).

With a view to such a methodological reading and study of the Upanishads, I would argue – drawing on our previous examinations

of the nature and use of ideas of reason in Parts 2 and 3 –

that brahman is properly understood as a limiting concept, that is, as a projected endpoint towards

which we can direct reflection on what we take to represent

valid knowledge and rational practice. We have discussed the

notion of ideas as limiting concepts or projected endpoints

of thought earlier (see Ulrich,

2014a, p. 7 and note 5, and 2014b, pp. 23-28); suffice

it to recall that reason needs such notions as reference points

for its critical business, however problematic they are bound

to remain due to their exceeding the reach of possible knowledge.

They thus pose a double challenge to reason. Reason needs to

employ them for critical ends while at the same time learning

to handle them critically, that is, to keep a critical stance

towards any claims based on their use. Again, as with the striking

parallels we observed before, I see no essential methodological

difference in this regard between the Upanishads' brahman and

Kant's ideas of reason. Consequently, a further conjecture

offers itself: we might try to embed Upanishadic reflection

on knowledge as inspired by the notion of brahman – "brahmanic

reflection" as it were – in the same kind of double or

cyclical movement of critical thought with which we earlier

associated the pragmatic use or "approximation" of

Kant's ideas of reason, equally understood as limiting concepts.

The idea is that in this way we might gain a deeper understanding

of both, the movement of critical thought in question as well

as the methodological implications of the "brahmanic reflection"

just suggested. So much for a brief outlook. At present we are

not yet prepared for such a discussion, as we first need to

familiarize ourselves with the two other Upanishadid ideas that

we selected for examination, atman and jagat.

"Atman" A second

major theme is atman, a counter-concept to brahman inasmuch as it

focuses on the individual that seeks to know or experience brahman, rather than

on brahman itself. Atman stands for the subjective side of the quest for knowing

brahman. If brahman is the Upanishadic symbol for objectivity,

atman is the symbol for subjectivity. Or, in the terms we used

in the introductory essay, atman embodies the emerging knowing

subject of the Upanishads, whose search for understanding

what is real and reliable in this ever-changing world – where

to find that basic, unchanging reality called brahman – leads

it to discover its own consciousness and self-reflection. "Atman,

or the Self, is the consciousness, the knowing subject, within

us." (Nikhilananda, 1949, p. 52). As the Upanishadic thinkers

understood centuries before the early thinkers of the Occident

(e.g., the pre-Socratic philosophers of nature, such as Anaxagoras

and Democritus, and later Plato and Aristotle), the key to understanding

our (for ever imperfect) grasp of the objective world lies in ourselves, in our consciousness

and, as a contemporary Western perspective might want to add, in our individual

and collective unconscious or subconscious (see Jung, 1966,

1968a). Early on the ancient Indian sages understood that both

brahman and atman – the objective

and the subjective principle – are indispensable notions for

reflecting on the sources and nature of human knowledge or error, even

if both notions are ultimately beyond human grasp. Likewise,

they recognized that neither notion is independent

of the other; each manifests itself in the other but cannot be reduced to it. "The

Absolute of the Upanishads manifests itself as the subject as

well as the object and transcends them both." (Sharma,

2000, p. 25).

Root

meanings The word

atman quite obviously contains the Sanskrit root of the

contemporary German verb atmen = to breath (also compare the German

masculine noun der Atem = the breath, a word that in contemporary German

is still also used in metaphoric or spiritual expressions such as der Atem

Gottes, meaning the creative presence of God's spirit]. The Sanskrit word in

turn is variously derived from the two Sanskrit roots "an" (= to breathe) and

"at" (= to move), two root meanings that come together in the act of

breathing in and out. Note that for phonological or declensional reasons, the initial "a" is suppressed in some uses, yielding 'tman.

This happens frequently when the term appears in

compound words following a vowel. Employing the phonetically reduced form along

with the complete form may help in consulting the Sanskrit

dictionaries, but otherwise need not concern us here.

Table 2

lists the entries of Monier-Williams

(1899) for both forms. Readers wishing to verify these entries may like to know

that the on-line search tools of the Cologne

Project (1997/2008 and 2013/14) and Monier-Williams et al. (2008) currently

only list tman

and under this entry do not include all the meanings given in the original

dictionary for atman; the latter are accessible through the online facsimile

edition listed in the reference section under Monier-Williams

(1899). Easier to use and more complete in this respect are some

of the other Sanskrit dictionaries, particularly Apte (1965/2008)

and, with some reservations regarding completeness, Böhtlingk and Roth (1855, p. 3-3f) and Böthlingk

and Schmidt (1879/1928, p. 3-045). For reasons of consistency,

Table 2, like the previous Table 1 (for "brahman")

and the later Table 3 (for "jagat"), relies on

Monier-Williams and focuses on the root meanings of "atman."

Some of Apte's additional translations will be mentioned in

the subsequent text. As in the case of Table 1, I have again highlighted some of the meanings of

special interest to us.

|

Table 2: Selected meanings of

[a]tman

(Source: Monier-Williams, 1899,

pp. 135 (f. atman) and 456 (f. tman), abridged and simplified)

|

|

atman, atmán, m[asculine

gender]. atman, atmán, m[asculine

gender].

essence, nature, character, peculiarity (often at the end of

a compound, e.g. karmA^tman).

|

(variously derived from an, to breathe; at, to move; vA, to blow;

cf. tmán) the breath.

|

the soul, principle of

life and sensation.

|

the individual

soul, self, abstract individual.

|

the person or whole body considered as one and opposed to the separate

members of the body. |

(at the end of a compound) "the understanding, intellect, mind" (cf.

naSTA^tman, deprived of mind or

sense, p. 532).

|

the highest personal

principle of life, Brahma ( cf. paramA^tman) .

|

effort, (= dhRti), firmness.

|

|

|

|

tman, tmán

m[asculine gender]. |

|

(= atmán) the vital

breath.

|

|

one's own person , self; 'tman after e, or o

for atman. |

|

Copyleft  2014 W.

Ulrich 2014 W.

Ulrich |

Derived

meanings In addition, Apte's (1965/2008) Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary lists

the following (among other) uses of the term “atman,” all of

which relate to both cognitive and emotional qualities,

to the mind and the soul: "thinking faculty,

the faculty of thought and reason" (p. 323); "spirit,

vitality, courage" (p. 323); "mental quality"

(p. 323); further, in derived and compound phrases, atman

also stands for qualities or efforts

such as "striving to get knowledge (as an ascetic), seeking spiritual knowledge"

(p. 324); "dependent on oneself or on his own mind,

self-dependence" (p. 324); "self-control, self-government"

(p. 325); "knowing one's own self (family etc.), knowledge of the soul, spiritual knowledge"

(p. 325); "practicing one's own duties or occupation,

one's own power or ability, to the best of one's power"

(p. 325); and, apparently accompanying such qualities,

forms of personal

conduct such as "self-purification" (p. 325),

but also "self-praise" and "self-restraint" (p. 325).

Personal reading The etymological

root meaning

of atman, so much is clear, refers to the activity of breathing – the

vital breath – as a source of vitality that keeps us alive and moving

and also allows us to grow and develop as individuals, to unfold our nature and essential character (compare the compound

word jivatman, also spelled givatman, from jivá

= "living, existing, alive" and tman, thus yielding "the

living or personal or individual soul," cf.

Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 422f, facsimile

edn. only).

Atman is thus also the source of our becoming what we have the potential to be

spiritually and intellectually, if only we undertake

the required effort of learning,

by seeking to know brahman and thereby also to better know ourselves, that

is, the individual self

of which both our soul and our intellect are constitutive.

Müller's (1879, e.g., pp. xxx) preferred translation of atman is indeed the

"individual self"

or simply the "self," meaning the essential core of

a human subject that lies behind the empirical individual as

it manifests itself in the phenomenal world, the aham

(cf. the German ich, "I") or "ego, with all its accidents and limitations, such as sex, sense,

language, country, and religion." Atman, the individual

self, thus distinguishes itself from both the empirical ego

(aham) on the one hand and the universal

or highest self (brahman) on the other hand. Atman is neither

aham nor brahman; rather, it is on the way from aham

to brahman, developing its contingent, empirical self towards

its essential, divine self. With respect to the latter, Müller

emphasizes that atman is always

"a merely temporary reflex of the Eternal Self"

(1879, p. xxxii; cf. his full discussion on pp. xxviii-xxxii). Atman's fundamental

task is to realize itself

– its individual self – in the double sense of achieving awareness

(recognizing it) and growth (developing it), so that this individual

self can become a fuller reflex of that higher, universal Self

of which it is only an imperfect reflection.

The core topic of the Upanishads,

as I understand it, is accordingly "to explain the true relation between brahman,

the supreme being, and [atman,] the soul of man"

(Müller, 1904/2013, p. 20). Atman's

self-realization, in the double sense just explained, is gained through the effort

to get to know brahman. The Upanishads therefore also

refer to brahman as paramatman (or parama-atman, from

paramá = most distant, highest, best, most excellent,

superior, with all the heart, and tman, yielding "the supreme spirit,"

Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 588):

paramatman is the ideal towards which jivatman, the living

self, is to strive, a process of realizing one's individual

nature and potential that has as its endpoint the convergence

of atman with brahman, or atman's becoming atman-brahman.

When this happens (in the ideal, that is), atman has found "its

very self," "that [self] which should

be perceived" or realized (Olivelle's apt translation of

"atman" in the Mandukya Upanishad, see 1996,

p. 289f, see verses 7, 8 and 12; italics added).

The

distinction, and ideal convergence, of atman and brahman is also related to the fundamental

notion

in Hindu thought of a perpetual cycle of rebirth and transmigration

of souls (samsara): atman can only free itself

from samsara by moving closer to brahman, that is, by realizing its own

highest

self. In connection with the notion of samsara,

atman's self is "the eternal core

of the personality that after death either transmigrates to

a new life or attains release (moksha) from the bonds

of existence" (Encyclopaedia

Britannica, 2013a). Which one of the two options will come true

depends on the degree to which atman realizes its individual

self in terms of both awareness and growth.

Atman

or the search for personal growth

We are, then, talking about the individual self

as-it-has-the-potential-to-be rather than as-it-actually-is;

about a person's vital self; about the ultimate source of

its being spiritually, emotionally and intellectually alive and growing.

Hamilton (2001, p. 28 and passim) similarly speaks of atman

as embodying "the nature of one's essential self or soul," and

Ganeri

(2007, p. 3) of a "healthy self" towards which

atman is to strive. Partly similar notions of personal growth are quite familiar to the

Western tradition of thought. I am thinking of Carl Rogers'

(1961) process of becoming and particularly of

C.G. Jung's (1968b) process of individuation, a process through which

a person's unconscious and conscious become one in the Self,

whereby the latter concept (the Self) is understood as the archetype of psychic

wholeness or totality. The difference is that in the Hindu tradition, this process

reaches beyond all the limitations and contingencies of a person's life

and takes on a truly cosmic dimension: the

individual soul or consciousness is expected to become one with the whole

universe as if individual awareness could ever include the whole of reality

or, in Vedanta terms, as if atman could ever be one with

brahman so as indeed to become atman-brahman.

Atman

or the quest for realizing the ideal in the real

Atman's

striving to become one with brahman: what

a great image for the eternal tension between realism and idealism

in the human quest for coming to terms with the world and, inseparable from it,

for becoming (or realizing) onself! Remarkably, in this Upanishadic image the tension can be resolved

in favor of a meaningful convergence – of the human condition

as it is and human development as it might be. Such convergence is conceivable in the Upanishadic

framework as it sees the ultimate ground of the person (one's

self-concept) in close interaction

with the cosmic principles (brahman) that pervade the universe and thus also shape

our awareness of the world and of ourselves. The tension between the real and the ideal is thus

reconciled in the notion of a fundamental union of individual (or

subjective) and universal

(or objective) principles.

Kant's later attempt, in the first

Critique, to explain

how the human mind can grasp and understand the world at all, or in

his terms, how the

mind's a priori categories can be constitutive of empirical knowledge, lead him to a similar solution: the answer must be that there exists

an

ultimate convergence of the human mind's internal structure and principles with those

of the universe (see Kant's highly differentiated analysis in

the "Analytic of Principles," 1787, B169-315,

esp. B193-197). The principles governing the world

must be the same as those governing the human mind! For purely methodological

reasons, Kant is thus compelled to postulate an ultimate unity of the cognitive

conditions that account for the intelligibility of the world with the

ontological conditions that account for its reality, a postulate he calls

the "highest principle of all synthetic judgments" (1787, B197):

We

assert that the conditions of the possibility of experience

in general are likewise conditions of the possibility of

the objects of experience, and that for this reason they

have objective validity in a synthetic a priori

judgment. (Kant, 1787, B197)

If as

humans we can grasp reality at all, infinite as it is and reaching beyond our

experience, it is because it is already in us, as an intrinsic part of our

cognitive apparatus. In the language of the Vedanta: atman can hope at

least partly to grasp the universal reality that is called "brahman"

because brahman is already in atman's soul, is part of its essential

nature. "The real behind empirical nature is the universal spirit within."

(Mohanty, 2000, p. 2). Atmavidya (the seach for

understanding oneself) and brahmavidya (the search for

understanding universal reality) go hand in hand.

From

cultivated understanding to cultivated practice Shifting

the focus from the realm of theoretical (speculative) reason

to that

of practical (moral) reason, I find a similar parallelism between

the deepest ideas of the traditions of Western

rational ethics and ancient Indian thought. Just as Kant's "enlarged thought," the rational

effort of taking into account

the implications of one's subjective maxim of action for all

others and thus to cultivate a sensus communis (see the

earlier discussion in Ulrich, 2009b, p. 10f, and 2009d,

p. 38), converges with the

quest for cultivating one's moral self, so

cultivated understanding of the world and individual self-cultivation

also converge in the ancient Indian tradition. In Vedanta

terms as well as in Buddhist terms, which in this regard do

not differ, "philosophical inquiry and the practices of

truth are also arts of the soul, ways of cultivating impartiality,

self-control, steadiness of mind, toleration, and non-violence."

(Ganeri, 2007, p. 4, added italics).

But

of course, effort and achievement are not the same thing. We are talking here about an ongoing process of cultivating one's

knowledge, character, and practice, rather than about

an accomplishment. Despite the promise of brahman's residing

in the individual, atman is only and for ever on the

way to self-knowledge and self-realization. The situation

resembles that of a student challenged by the teacher to never

stop learning; or, in the previously quoted terms of Müller,

of a pupil

who is called upon to learn to know his Self rather than

just himself, that is, to understand

his individual self as "a

merely temporary reflex of the Eternal Self" (Müller, 1879, p. xxxii).

Once we realize that self-knowledge (atmavidya) is quite

impossible without knowledge of that highest expression of Self

called brahman (brahmavidya), and vice-versa,

the challenge is unavoidable:

The

highest aim of all thought and study with the Brahman of the

Upanishads was to recognize his own self as a mere limited reflection

of the Highest Self, to know his self in the Highest Self, and

through that knowledge to return to it, and regain his identity

with it. Here to know was to be, to know the Atman was to be

the Atman, and the reward of that highest knowledge after death was freedom from new births, or immortality.

That

Highest Self which had become to the ancient Brahmans the goal

of all their mental efforts, was looked upon at the same time

as the starting-point of all phenomenal existence, the root

of the world, the only thing that could truly be said to be,

to be real and true. As the root of all that exists, the Atman

was identified with the Brahman. (Müller, 1879, p. xxx)

Accordingly,

as Müller sums up the gist of the Upanishads, the question

that may guide us in reading these bewildering, mythical, partly

dark and almost unintelligible, yet partly also bright and illuminating

texts is this:

The

question is, whether there is or whether there is not, hidden

in every one of the sacred books, something that could lift

up the human heart from this earth to a higher world, something

that could make man feel the omnipresence of a higher Power,

something that could make him shrink from evil and incline to

good, something to sustain him in the short journey through

life, with its bright moments of happiness, and its long hours

of terrible distress. (Müller, 1879, p. xxxviii)

The human being's

striving

beyond the fragmentary universe within which

it moves in everyday thought and practice, towards something deeper or higher, towards something that

could "lift the heart up"; that's what well-understood self-knowledge (atmavidya)

is all about from a Vedantic perspective. It leads us directly

to the third

selected idea that I find so interesting in the Upanishads' account

of the general (or universal) in all human cognition and practice,

the concept of

jagat.

"Jagat" At first glance, it may look as if this one were

the easiest of the three ideas to grasp, as the term is still

used today in many regional Indian languages for referring to

the experiential world in which we live. On closer inspection

though, it is perhaps the most complex and interesting of the

three concepts, at least from a methodological (rather than

spiritual) point of view. The reason is, I believe it can make

a significant difference to our competence of "enlarged

thinking," or more specifically, to our understanding of

the general in the particular and vice-versa and accordingly,

to our skills in dealing constructively and critically with

the eternal tension (or dialectic) in human thought and practice

mentioned above, between the real and the ideal – the

idealist and the realist sides of our grasp of reality. But

let us see.

Root

meanings The

Sanskrit root term contained in the second syllable of "jagat" is ga, which refers

to moving, going, not too different from the English go; whence comes

the Sanskrit

verb gam, = to go, move, or approach; to arrive at,

to accomplish or attain (see Wilson, 1819/

2011, p. 282). The prefix ja in the first

syllable means as much as "born or descended from, produced

or caused by, born or produced in or at or upon, growing in, living at,"

therefore also "son of" or "father of,"

or "belonging to, connected with, peculiar to" (Monier-Williams,

1899, p. 407);

it can also mean "speedy, swift" (the only meaning

given by Wilson, 1819/2011, p. 336, whereas Monier-Williams

lists it almost last of the many meanings he gives) or "victorious,

eaten" (Monier-Williams,

1899, p. 407), two meanings that point to the term's connotation

of chase or hunt (Jagd in German). The prefix may also be related to the similar term ya, which among

other meanings refers to that which moves or to "who goes, a

goer, a mover" or also "air, wind" (Wilson, 1819/2011,

p. 677, similarly Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 838). So jagat

is everything that is moving or movable, undergoing variation, in flux, "especially in the sense

that no fixed description of it will ever be correct" (D.P. Dash, 2013a). Here

is, once again, a

representative selection of meanings from the Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary

(Table 3):

|

Table 3: Selected meanings of

jagat

(Source: Monier-Williams, 1899,

pp. 108 and 408, abridged and simplified)

|

|

jagat, jágat m[asculine]

f[eminine] n[euter] gender. jagat, jágat m[asculine]

f[eminine] n[euter] gender.

moving, movable,

locomotive, living. |

|

jagat, jágat m[asculine

gender]. |

|

air, wind. |

|

pl[ural use]. people , mankind. |

|

jagat, jágat n[euter]

gender. |

|

that which moves or is

alive, men and animals, animals as opposed to men,

men. |

|

the world, esp. this

world,

earth. |

|

people, mankind. |

|

the plants (or flour [ground

grain] as coming from plants) |

|

the site

of a house |

|

the world, universe |

|

du[al number]. heaven and

the lower world |

|

pl[ural use]. the

worlds (= [ja]gat-traya ["three jagats"]) |

|

jagad-atman,

jagadAtman m[asculine gender].

[also

jagat-atman,e.g.,

Apte (1890/2014, p. 503)] |

|

world-breath. |

|

wind; world-soul. |

|

the Supreme Spirit

[lit. = world spirit]. |

|

Copyleft  2014 W.

Ulrich 2014 W.

Ulrich |

Against the background

of the discussion thus far, it is interesting to

note that jagat refers

not only to the "world," "earth" or "universe"

in general but can also take the specific meaning of "this

world [of ours]" (Monier-Williams, 1899, p. 408).

Jagat is the world as it manifests itself to the individual

(atman) as a perceived or imagined reality, a perception that

is in constant flux and does not usually capture the full, objective

reality (brahman). Further, in addition

to the manifest physical world, jagat may also refer specifically

to "the world of the soul, [or of an individual's] body" (Apte,

1965/2008, p. 722; cf. 1890/2014, p. 503). Jagat can thus

refer to different realms of the universe, such as

heaven and earth. The compound nouns trijagat and jagat-traya

designate the Vedantic conception of three worlds, either as "(1) the heaven, the atmosphere and the earth" or as

"(2) the heaven, the earth, and the lower world" (Apte,

1965/2008. p. 789;

similarly Böthlingk and Roth, 1855,

p. 3-428, and Böthlingk and Schmidt, 1879/1928, p. 3-49).

As a last hint, Apte also lists jagat as a grammatical

object of

the verbal noun nisam (lit. = not speaking, silent, observing),

which refers to the act of "seeing, beholding, [having]

sight [of]"; accordingly the phrase nisam jagat stands

for

"observing the

[visible] world" and, as a result, having a certain

"sight" of the world (p. 924, cf. 1890//2014,

p. 638).

Derived

meanings: the

rich etymology of "jagat" While the Sanskrit-English dictionaries on which I have drawn have their

strength in a scholarly documentation of actual occurrences

of Sanskrit terms in the ancient literature, they are less strong

when it comes to explaining how old Sanskrit terms have found their way into the

contemporary

vocabulary of Indo-European and other languages. "Jagat"

is such a term. It continues to be used in several Asian

languages, including Modern Standard Hindi, in meanings related to land,

earth, world, or universe, with a number of different derived

connotations.22) Likewise,

in the European languages (esp.

in Dutch and German) one can find numerous contemporary words and entire word families that appear

to be related to the ancient Sanskrit jagat. They often

go back to the Old-Germanic root jag, which apparently contains

the Sanskrit root terms ja and gam (as explained

above) and means

as much as "moving fast, chasing." Here are three examples

of such word families, all of which are of particular interest to our present

discussion.

(1)

The German noun Jagd (= the hunt) derives directly from

the Middle High German noun jaget or jagat.

This etymological connection makes the combination of the two above-listed,

at first glance unrelated, root

meanings of the prefix ja understandable, of "speedy, swift"

along with "victorious, eaten." Interestingly, the German noun originally referred not only to the activity of hunting but

also to the parties involved or admitted (a meaning it still

has today, although it is now rarely used in this sense), as well as to the

area in which hunting was permitted. The corresponding German

verb is jagen (= to hunt, figuratively also to move fast

or to chase something or somebody). Similar forms exist in

other North-European languages (e.g. the Dutch verb jagen,

from Middle Dutch jaghen, Old Dutch jagon; likewise

Swedish jaga or Swiss-German jage).

The Dutch noun for Jagd is jacht (from Middle Dutch jaght),

which is obviously related to the German and Dutch term for

a sailing yacht, Jacht (= yacht, originally a fast moving

boat or "hunting boat").

(2)

The Swiss-German noun Hag (= fence, originally meaning

as much as a thorn hedge that encloses a piece

of land or forest) goes back to the Old High German hac

and further to the Old Germanic (Proto-Germanic) hagatusjon,

with many derivatives such as hagaz

(= able, skilled), hag or haga (= to beat,

push, thrust, cf. the contemporary English verb "to hack,"),

and häkse (= a witch, cf. Middle English hagge,

Dutch heks, German Hexe). Although the link is not definitively

proven,

both the form and the meaning of these and other words

with the root term hag are strikingly close to jag[at]; they

all connote some aspects of fast movement or hunting (e.g.,

chasing, stinging, hitting, capturing, fencing in). These

connotations are still very apparent, for example, in the contemporary

German verbs hacken (= to chop, hack; also

abhacken = to chop off) and einhagen (= to hedge,

to fence in), as well as in the German nouns Hecke (=

a hedge, related to the Old English haga = an enclosure,

a fenced-in area, and to the Middle English hawe as in

hawthorn) and Gehege (= an enclosure, preserve, a

fenced area of natural preservation or also an artificial habitat

for animals as in the zoo).

(3)

In other derivatives, the root meanings of chasing, capturing,

enclosing, and delimiting take on a strong connotation of protection,

as in

the German verb hegen

(orig. = to hedge), which now means as much as to care for, look after, cultivate,

or foster (as in the phrase hegen und pflegen, to lavish

care and attention on somebody or something). Figuratively used

it means, for example, to nurture a hope (eine Hoffnung hegen), to

entertain an expectation or a doubt (eine Erwartung hegen,

einen Zweifel hegen),

or to pursue an intention or plan (eine Absicht hegen, einen

Plan hegen). Another derivation appears to be

Hain, an old-fashioned German noun that is now chiefly

used in poetic

language for a grove but which originally just meant a piece of land surrounded by trees or bushes, yielding a natural delimitation for an orchard or

garden, a resting place, or a small farm or other kind of dwelling.

This explains why the root hag is also still frequently found today

as a component in

the names of plants that are characteristic of such places (e.g.

Hagedorn = hawthorn, from Old English hagathorn), or Hagebutte = rose hip), as well as in

many old place names (e.g., Hagen and Im

obern Hag in Germany, Den Haag in the Netherlands, or Hagnau

in Switzerland).

To

judge from the numerous etymological sources that I have consulted, ranging

from the Oxford English Dictionary to Wiktionary for

English and from the Duden to the Kluge and the

Wahrig dictionaries for German, it appears that the

link between jagat and the first-mentioned word family

around Jagd is firmly established,

whereas the precise history of the modern words mentioned under points (2) and

(3) lies partly in the dark. Even so, the extent to which the

root meanings of these terms agree with those of the ancient

Sanskrit word jagat is striking. We may sum up these

root meanings as follows:

(1) the activity of movement or

chase; an object that moves or undergoes change;

(2) a piece of land or

site of a dwelling, or that which delimits it;

(3) an element of care, attention, interest or cultivation;

this world of ours or a delimited part of it about which we care.21)

A

second observation that I find striking is this. As a common

denominator, all three root meanings have to do with the core notion

of something bounded or limited that changes and can be changed but which is also being cared for – a

core notion that I associate with my methodological interest,

in my work on critical systems heuristics (CSH), in the role

of boundary judgments and hence, of boundary discourse and boundary critique

as tools for cultivated understanding (for an introduction see, e.g., Ulrich 1996,

2006a, 2001, and 2005). However, for the time being, let us stick to the etymology of jagat.

Personal reading Considering the

various meanings of jagat, I conclude that it may stand for virtually any object-realm of experience or awareness (and,

in the case of humans, also of

thought, discourse, and action) that constitutes the "world"